Henri Matisse: Drawing with Scissors, Part II

"The importance of an artist is to be measured by the number of new signs he has introduced into the language of art." —Henri Matisse to Louis Aragon, Thèmes et Variations, "Matisse-en-France," 1943

Up to 1940, Matisse's cut-out method had been used as an implementation tool for envisioning and preparing large-scale works that would have been too large to repeatedly paint in the search for a final composition. Over time, however, he would come to appreciate the cut-out method as an intermediary between drawing and painting (and even sculpture). It would become an artistic language in its own right.

The Cut-Outs: A Utilitarian Function

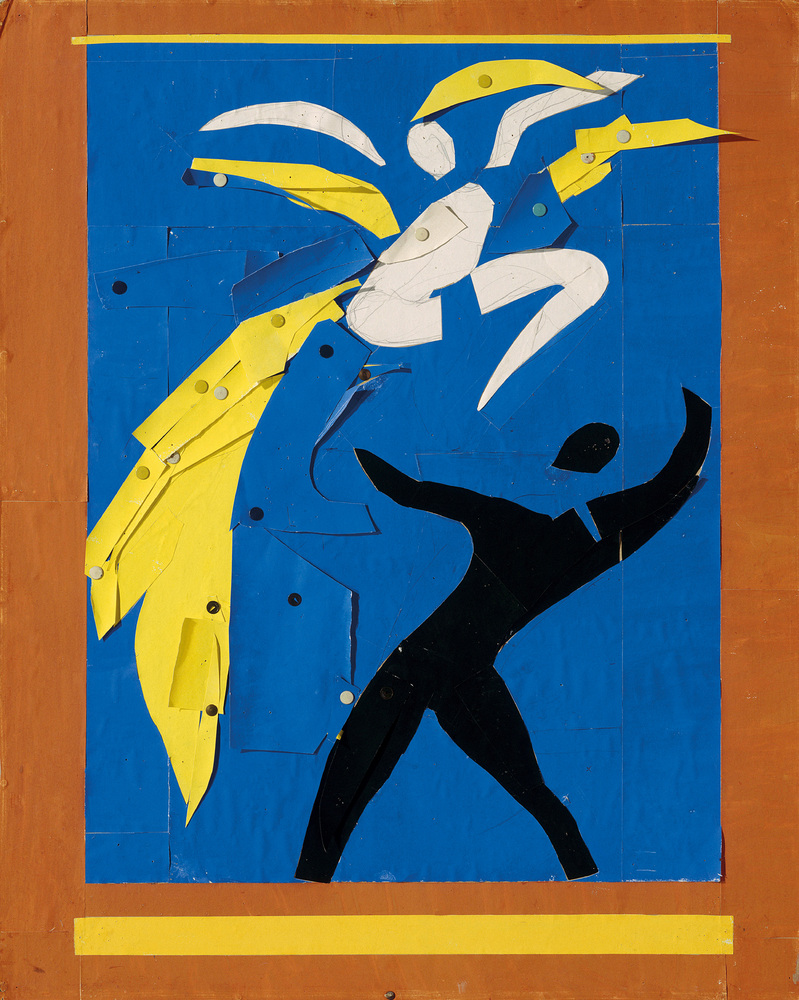

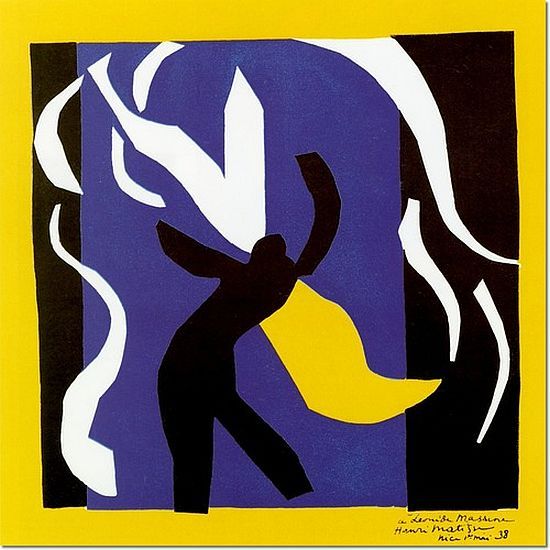

Matisse's first use of the method goes as far back as 1919 when he designed the costumes and set for the Ballets Russes production, Le Chant du Rossignol. More famously, he incorporated cut-outs in his preparatory phase for his Barnes Mural commission (1931-33) and for another Ballets Russes costume and set design production, Rouge et Noir (1934-38).

Biographer Hilary Spurling recounts Matisse's adoption of a "new" method for preparing the Barnes mural:

Setting aside his brushes, he hired a professional housepainter to cover sheets of paper in the four colours finally selected, producing a stack of painted paper in flat, uninflected black, grey, pink and blue that could be pinned onto the canvas. Matisse now drew and redrew his entire design, outlining shapes on coloured paper for an assistant to cut out with scissors.

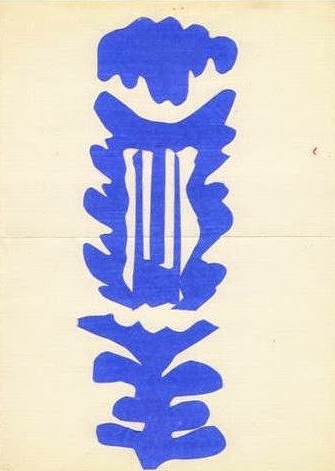

The Lyre: No Function, Pure Form

"Finally, he made a cut-out, 'The Lyre,' a small thing, blue on white, and said 'it's my first cut-out' that is to say, a well-thought-out work, which he succeeded in investing with feeling. That was the start." —Lydia Delectorskaya, Matisse's assistant in his late years, as quoted in Samantha Friedman's "Avant la lettre"

There came a moment when the cut-outs ceased being for something (for painting, or the stage, or for process). Instead, Matisse began to see his cut-outs as works of art in themselves: pure expressions of line and color. Looking back on this time in an interview with André Verdet in 1952, Matisse explained :

What I was trying to do with these paper cut-outs was to rediscover, through unusual technical means, the lovely days of line and color, to wring out of them the resonance and concurrent of a new freshness…

While his assistant Lydia Delectorskaya identifies The Lyre (1946) as the first "true" cut-out, it is not quite clear what would have distinguished these visual representations from his earlier cut-out work for the magazine Verve and the publication of Jazz. Although Jazz was published in 1947, many of the images had been completed between 1943-1944. Recovering from his illness and confined to bed for much of the time during the war years, Matisse took advantage of the cut-outs' small scale and ease of material.

What, then, might distinguish The Lyre from those rich bursts of cut color in Jazz and Verve? Perhaps the 1943-44 cut-outs show a Matisse who is still painting with paper. He cut with a paintbrush, so to speak, to reveal compositions that may not have strayed so far from those in his paintings. Looking at his so-called "first cut-out," the master of composition and objects-in-relationship could see before him something quite distinct.

The Lyre broke into a new form of visual language not merely as a product, but also for its process. He explains in his 1952 interview with André Verdet:

But here is not a brush winding and gliding on canvas, but scissors cutting through stiff paper and color. The procedural conditions are completely different. The shape of the figure springs from the action of the scissors, which give it the motion of organic life. This tool, you see, does not modulate; it does not brush onto, but cuts into--a point that should be emphasized, for it makes the criteria of observation completely different. The new tool gives the artist who knows how to use it greater authority in dealing with shapes. The product is different.

So much of the joy that came with his "true" cut-outs seemed to stem from the freedom and spontaneity his scissors afforded him. As shared in Hilary Spurling's biography of Matisse, Anneleis Nelck described seeing Matisse in action:

'There is nothing to resist the passage of the scissors. Nothing to demand the concentrated attention of painting or drawing, there are no juxtapositions or borders to be borne in mind.'

When painting, Matisse could jump with the sense of flying. The cut-outs gave him wings.

A Bigger Canvas

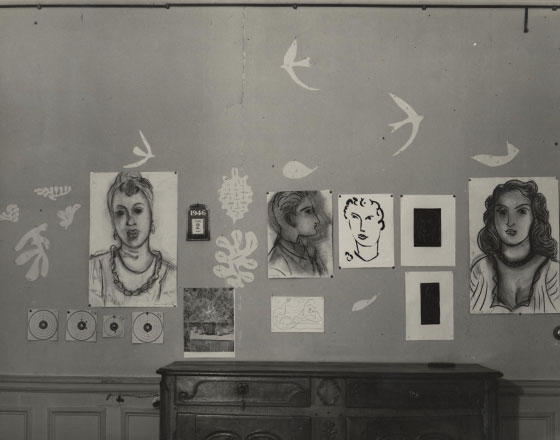

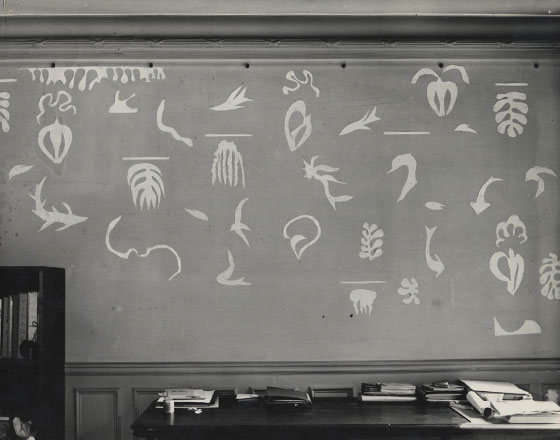

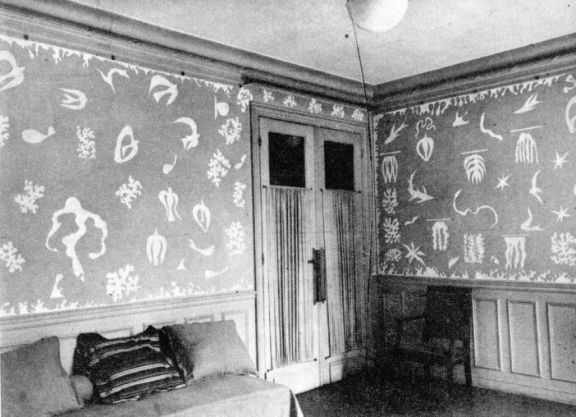

Just as revolutionary as Matisse found his Lyre to be, the act of pinning it to the wall also played an important role in the direction of his cut-outs. It did not take him long to transform his apartment walls into large canvases. His initial pinnings give the air of swirling leaves around other pinned drawings and pictures. The photographs below mark the transition from the wall as "bulletin board" to full-scale compositions.

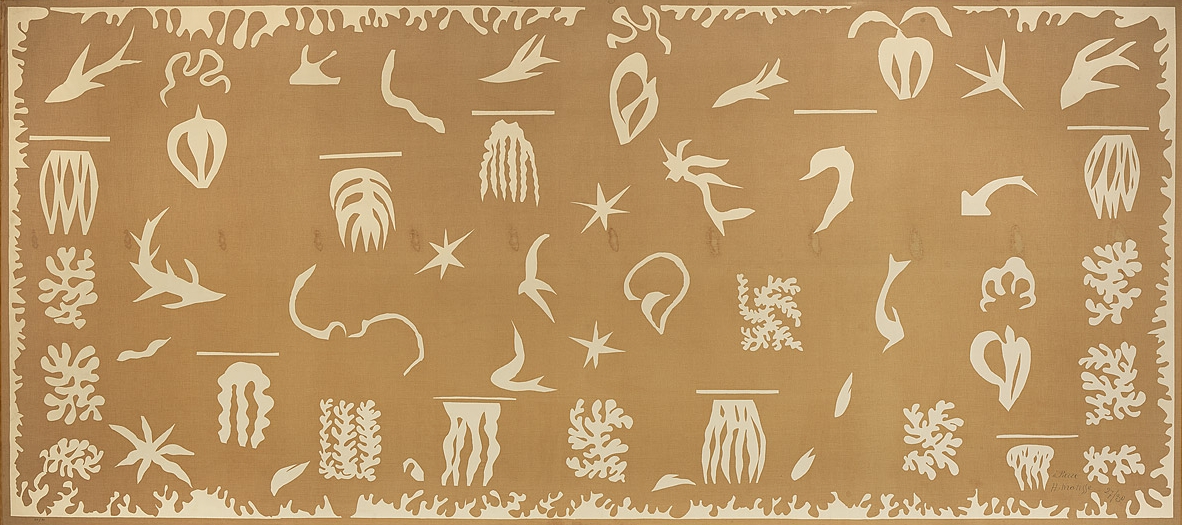

Oceania, the Sea (1946) and Oceania, the Sky (1946) were Matisse's first large-scale cut-outs. As recounted in "How Matisse's cut-outs grew on the walls of his Paris apartment," Matisse worked with textile manufacturer Zika Ascher to replicate the scale and texture of the designs as silkscreen prints.

Evolution into His Last Years

In the early 1930s Matisse first turned to the cut-outs as a means for envisioning large-scale murals and ballet sets. Fifteen years later, the cut-outs' provisionary qualities (their ability to be pinned and moved, trimmed or replaced) lent themselves to ever-more large scale projects. By 1948, he based his designs for the renovation of Vence Chapel off his cut-outs.

By 1953, the year of his death, his paintings (most of them about 9' x 9') take on a quiet boldness. From the man who seemed to fill every inch of his canvases with vibrant texture, these seem to suggest a different kind of vibrancy. They are memories.

*All works by Henri Matisse © Succession Henri Matisse

**Photographs of Matisse's Paris apartment by Hélène Adant courtesy of Matisse Archives.

Additional Resources

Read Henri Matisse: Drawing with Scissors, Part I for more background regarding the emergence of Matisse's Jazz cut-outs during an era that for Matisse was riddled with illness, war, and frustrations about drawing and painting.

The most comprehensive biography on Matisse is written by Hilary Spurling. Matisse the Master is the second volume in a two-part series and covers his most productive years as an artist, from 1909-1954.

Henri Matisse: The Cuts-Outs is filled with essays on the evolution of this style. A preview of the book includes the essay "The Studio as Site and Subject" and also includes a number of images from the era.

Matisse:A Retrospective is a rich trove of primary sources, including letters and interviews by Matisse.

The introduction to Jazz is handwritten by Matisse and includes his description of his cut-outs as "drawing with scissors." A thumbnail collection ("Gallery Guide") of the images is available from the Des Moines Art Center.

*Frontispiece

Henri Matisse (1937-8), Detail of Two Dancers, stage curtain design for the ballet Rouge et Noir, gouache on paper, cut and pasted, notebook papers, pencil and drawing pins (thumb tack), 31 5/8 x 25 3/8 in. © Succession Henri Matisse. Photograph by Iliana Gutierrez