Julia Child: The Scientific Notation of Cooking

“One of the secrets, the pleasures, of cooking is to learn to correct something if it goes awry; and one of the lessons is to grin and bear it if it cannot be fixed.” —Julia Child, My Life in France

Today, Julia Child is remembered as the high-spirited and passionate cook who transformed home cooking for the "average" American home chef. But it wasn't until her late thirties that she discovered this love of food and cooking. As a latecomer to the art of preparing a good meal, Julia Child relied on learning from teachers, following recipes, and asking experts—the butchers, fromagers, and bakers with whom she would come into everyday contact.

By the time she joined forces with her two French colleagues to write the book that would eventually become Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Julia was determined to create a book full of recipes that could be consistently replicated, and which would also teach home cooks the basic methods and techniques of cooking. She was a firm believer in process, trial and error, and in learning from (but not apologizing for!) one's mistakes in cooking.

Vision: Working Towards a Goal

"I liked to strip everything down to the bones; with a bit of work, I thought this book could do that, too, only on a much more comprehensive scale. I had come to cooking late in life, and knew from firsthand experience how frustrating it could be to try to learn from badly written recipes. I was determined that our cookbook would be clear and informative and accurate, just as our teaching strove to be." —Julia Child, My Life in France

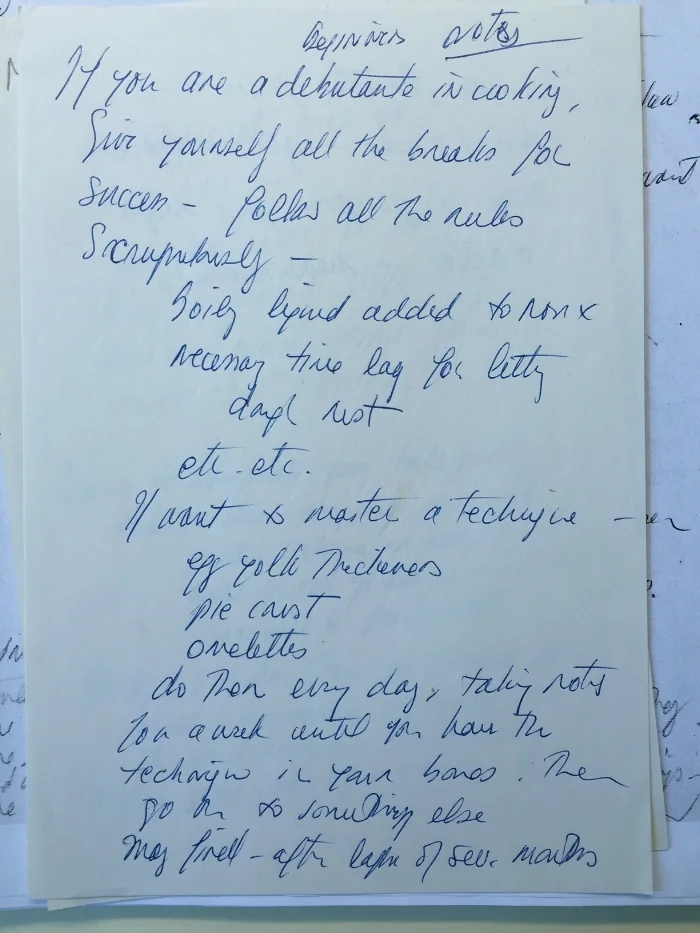

In order to produce the kind of cookbook she envisioned, Julia was committed to testing the recipes she and her French colleagues created and analyzing why something did or did not work. This commitment would serve as her guiding methodology and also secured her confidence in the value of producing such a book. Her vision was put to practice through the rigorous testing of recipes and analysis that came with note-taking and trial and error—a process she referred to as her "operational proof."

Process: The Operational Proof

"In the meantime, I had been working on my ‘hen scratches’—my collection of recipes. I was amazed to learn, upon close inspection, how inexact many of the recipes in well-regarded books were, and how painfully exact ours must be to be worth anything at all. Each recipe took hours of work, but I was finally getting them into order." —Julia Child, My Life in France

In Julia's eyes, part of the success of the cookbook would rely on home cooks being able to replicate her recipes just as if they had been served by her in her own French kitchen. To do this, she and her colleagues researched the differences between French and American ingredients and translated measurements proportionately from grams to teaspoons, cups, and tablespoons. Julia paid special attention to writing out each necessary step, no matter how simple or implied a step may have seemed.

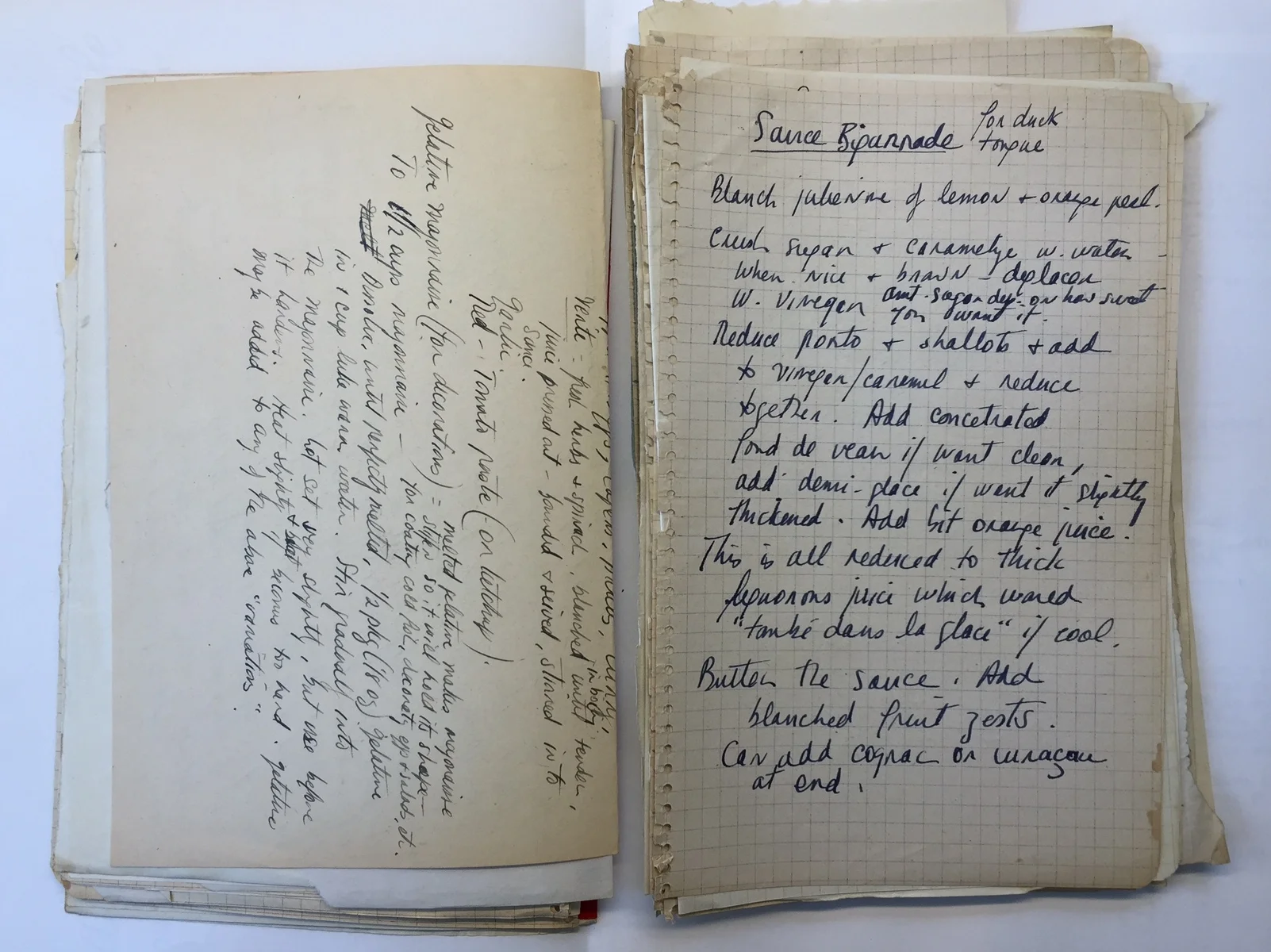

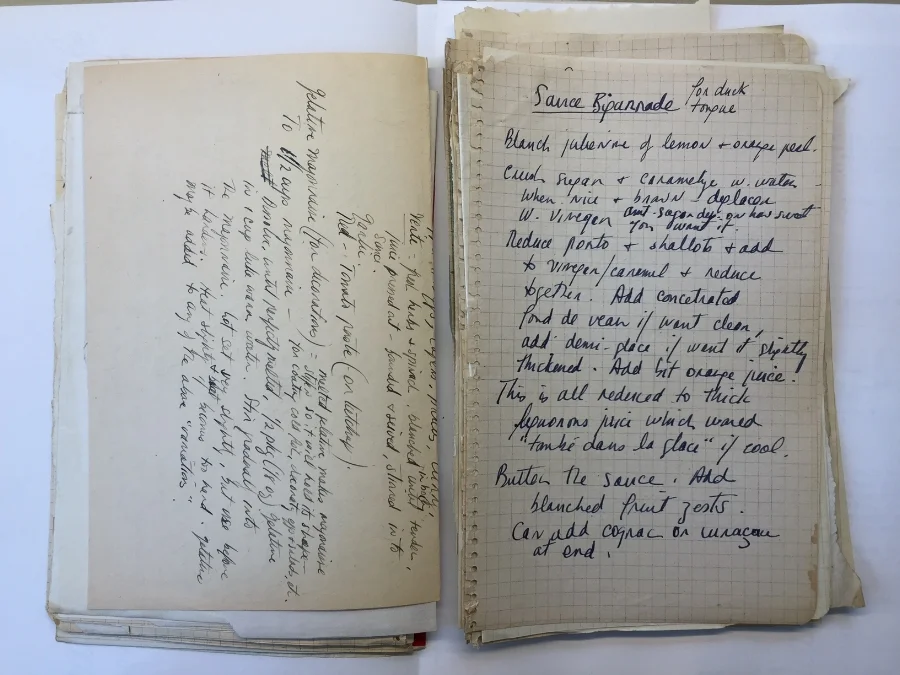

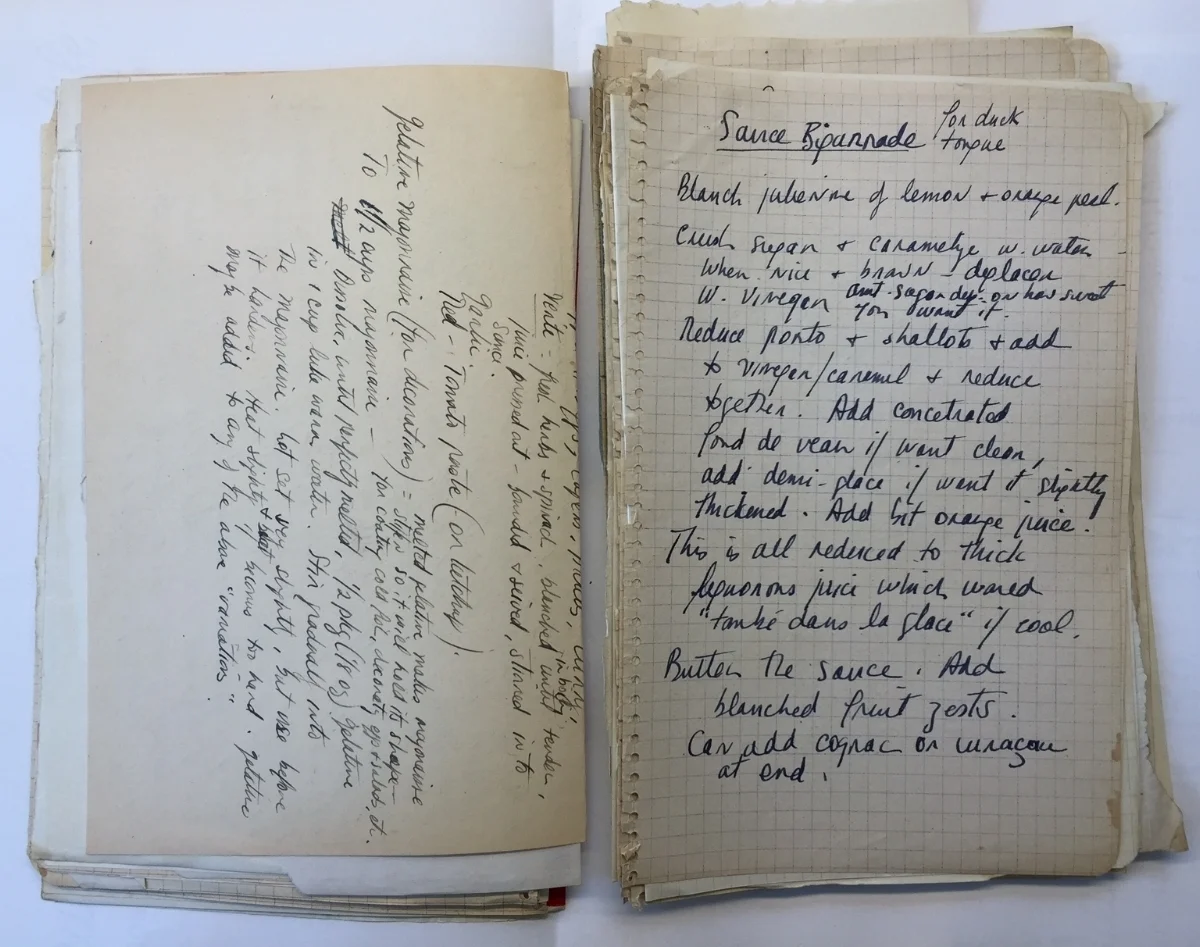

One way Julia tested her recipes was by asking her American friends to try out the recipes at home and offer feedback. The image below captures one of her "top secret" sauce recipes. She described her process in her memoir, My Life in France:

In the meantime, I sent three top-secret sauce recipes—for hollandaise, mayonnaise, and beurre blanc—to four trusted confidantes, for them to test in real American kitchens with real American ingredients. We referred to these ladies—Dort, Freddie Child, Dorothy Canfield Fisher, and Mrs. Freeman Gates (a friend of mine)—as our ‘guinea pigs,’ and asked them to try making each sauce just as we had described it and to give us honest feedback. ‘Our object is to explain “how to cook French for beginner and expert cooks,”’ I wrote in a cover letter. ‘Do you like our vocabulary? Do you care about such a book?’

Product: Preparing the Manuscript

"Writing is hard work. It did not always come easily for me, but once I got going on a subject, it flowed. Like teaching, writing has to be lively, especially for things as technical and potentially dullsville as recipes. I tried to keep my style amusing and non-pedantic, but also clear and correct. I remained my own best audience: I wanted to know why things happened on the stove, and when, and what I could do to shape the outcome." —Julia Child, My Life in France

In addition to testing recipes, a huge part of preparing the cookbook was the actual writing of the book. Reading through the cookbook, one finds useful information about selecting and handling ingredients.

Her archival records include pages of drafts for her memorable introduction to the "servantless American cook" in Mastering. Below you can see Julia rewrite a similar idea in various ways, searching for the right words while at the same time building the thought for herself.

Julia Child Materials © 2018. Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts.

Conviction: The Art of Determination

While today Mastering the Art of French Cooking has been reprinted at least 13 times, the book was originally rejected. Nonetheless, Julia believed in the book she and her French colleagues had created. She recounts in My Life in France:

Even though Simca and I were both putting in forty hours a week on The Book, it went very slowly. Each recipe took so long, so long, so long to research, test, and write that I could see no end in sight. Nor could I see any other method of working. Ach!

Even when Julia faced disappointment at the prospect of the book never getting published, she knew there had been value in the process. From My Life in France she shares:

I sighed. It just might be that The Book was unpublishable. I wasn’t feeling sorry for myself. I had gotten the job done, I was proud of it, and now I had a whole batch of foolproof recipes to use. Besides, I had found myself through the arduous writing process. Even if we were never able to publish our book, I had discovered my raison d’etre in life, and would continue my self-training and teaching.

After two publishing houses failed to see its potential, serendipity brought the manuscript into the hands of a young francophile gourmet and editor, Judith Jones, who after trying the boeuf bourguignon recipe at home reached out to Child and brought the book to publication. This would mark the start of Julia’s entry into the hearts and kitchens of American homes.

*Special thanks go to the Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts for their permission to post these documents. The photographed documents featured in this article belong to Julia Child Materials © 2018 and may not be reproduced. All photographs were taken by Iliana Gutierrez.

**The papers of Julia Child are stored at the Radcliffe Institute’s Schlesinger Library at Harvard University. Warm gratitude to the wonderful Schlesinger librarians who helped make this particular dive into research a rewarding experience.

Additional Resources

Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volume I is Julia Child’s first published cookbook; many more would follow. Julia wrote My Life in France late in life with her nephew Alex Prud’homme. It offers a rich portrait of Julia’s passion and process. As Always, Julia provides an intimate insight into the ups and downs of publishing Mastering. It highlights the important relationship Julia shared with Avis DeVoto and reminds us that friendship, support, and encouragement serve as special ingredients in bringing ideas to life.

*Frontispiece

Julia Child Papers, 1925-1993; recipe for sauce bigarnade, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, 1952-1989. MC 644, folder 763a-763b. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Julia Child Materials © 2018. Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts.

!["It is not enough that the 'how' [of making hollandaise or mayonnaise] be explained. One should know the 'why,' the pitfalls, the remedies, the keeping, the serving, etc." —Julia Child, My Life in France.Image from Julia Child Papers, 1925-1993; top…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5716a88ed210b8cd267f43a3/1531994080904-6T0HXKEZ16DVYHKPMIDX/Julia+Child+top+secret+sauce+hollandaise+recipe)