Xenos: A Composition by Akram Khan

"As tired bullocks and bull buffaloes lie down at the end of monsoon, so lies the weary world. Our hearts are breaking." —excerpt from WWI censored letter by an Indian soldier recruited to fight for the British empire

"What is it to be human when man is as a god on earth?" —Ruth Little, dramaturg for Xenos

Xenos: Performance

In Xenos, one man's body makes visible the sense of alienation that comes from historical erasure. Akram Khan's final solo dance performance presents us with the story of "X," no man and everyman, as a way of commemorating the 1.5 million Indian soldiers who fought for the British empire during World War I.

Xenos opens the final season of 14-18 NOW, the United Kingdom's five-year arts program to bring the stories of the First World War to life through music, performances, poetry, film, photography, and large-scale artistic installations. Both Xenos and the artistic productions from 14-18 NOW serve as excellent examples of how history can be made visible through art.

Xenos: Story

The scene opens with X, a shell-shocked Indian dancer, who begins to experience flashbacks while performing classical Indian kathak until he finds himself completely immersed in memory and the landscape of war.

Akram Khan's online "microexperience" of the performance delves into the process of creating the hour-long show, and provides videos of rehearsals with musicians and interviews with the team of people who helped create this project. Below is the synopsis of the performance:

Create your own microexperience by delving into various aspects of the process behind Xenos.

Xenos: Memory

One of the most interesting features of Xenos is its ability to take us beyond its own stage and onto an even larger one: that theatre of war. As part of the creative process, Khan and his team relied on archival material to get a sense of colonial soldiers' experiences. There are excerpts woven into the performance, but the history itself is made more vibrant by the remaining fragments of the archives themselves.

Nearly all of the public records that exist from WWI Indian soldiers, or sepoys as they were known, are now found as part of the British censorship office. Most letters passed through the post office in Boulogne, France, where a small percentage were read before being shipped out. Letters were read by a small team of officers and translators who then created reports of their findings. As scholar David Omissi stated in a lecture, most letters were mailed out unless they made reference to illicit behavior or passed on information that may have unsettled members back home.

One such rumor the office tried to quell, for example, was that of Indian troops being sacrificed to protect British troops. Codes were often adopted as a means of covertly relaying messages. One example of double meaning is shared by Bugler Mausa Ram:

The state of affairs is as follows: the black pepper is finished. Now the red pepper is being used, but occasionally the black pepper proves useful. The black pepper is very pungent and the red pepper is not so strong.

The British recruited heavily from illiterate, rural areas of India. This did not mean, however, that a written record was not left. They were, as scholar Santanu Das put it, "illiterate, but literary." To communicate, senders and receivers would solicit others to write and read the letters for them. This sense of public intimacy adds a particular layer to the visible trace left behind in these now mostly lost letters.

Censorship, too, contributed directly to the awareness of a more public audience than the intended beloved. Soldiers would have known that their letters might have been read before being shipped out, so messages were clouded in symbolism. "Think carefully as you read" or "Think about this" were phrases that often signaled to censors that a message was written in layers. One soldier, Pay Havildar Shadma Khan, is quoted in a censorship report (notes by the censor are made in parentheses):

"'I will now write about the war. It is now the month of Cheyt (Harvest month for the winter barley crop in Northern Punjab). There is a full crop of ripe barley. Crowds are gathering round the woman who parches the grain. She parches the whole lot at once. Her stove is very hot. I hope you will read very carefully what I have written so badly.' (By the woman who parches the groin he means the enemy.)"

Of course, symbolism could always have been misinterpreted. Other references were built into letters through old myths and nursery rhymes. Their significance would have been known to receivers but would have been lost to censors.

Xenos: Body

Xenos also captures the process of an aging dancer looking back on his years. For Khan, Xenos represented both a departure and a battle. He explains:

While I was creating XENOS, I felt I was not inspired by my own body anymore. I fought an inner battle with myself to get up every morning; my body was complaining all the time. It was reminding me every second that it is vulnerable and I hate that feeling. It gave me confidence once upon a time. I stood strong on it. But now my body has really shut down.

Memory, history, and body come together as commemoration for life, and with this, art makes loss visible.

Additional Resources

BBC Radio 4 presents a two-part program titled Soldiers of the Empire (Part I: "Recruitment and Resistance;" Part II: "The Fight in Fairyland").

The British Library's article "The Indian Sepoy in the First World War" by Santanu Das includes a brief history of the role of the sepoy with photographs and also provides first-hand documents from the censorship office. Pair this with David Omissi's article "Sepoy's Letters (India)"

Indian Voices of the Great War: Soldier's Letters 1914-1918 by David Omissi provides a comprehensive account of letters sent by sepoys from France.

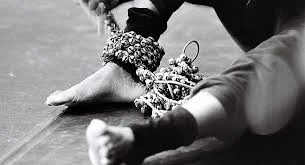

*Frontispiece

Akram Khan in Xenos at Sadler's Wells, London. Photo: Jean Louis Fernandez