Wright Brothers: A Flying Idea, Part II

"The ground under you is at first a perfect blur, but as you rise the objects become clearer." —Wilbur and Orville Wright, "The Wright Brothers' Aeroplane"

Ideas can seem rather intangible until they are finalized. This is why idea as object provides a unique view of tracking process; certain ideas depend upon the tangible. The Wright Brothers' careful documentation of their flying machines provides us with a proxy for analyzing how ideas morph over time.

One of the challenges of portraying process is that, most often, the point of such work is the final product. While the process itself is a necessary element of that work, it is typically a means for reaching the final goal. The intended audience and users of most final products have no need to witness the trials and cycles of work that go into creating the object. The deliberate documentation of process, therefore, may be kept from public view or even lost to time as its value is considered secondary.

The Wright Brothers, however, recognized that analyzing the process itself was crucial for moving ahead. In addition to photographing their ventures at Kitty Hawk and elsewhere, they also kept meticulous records through charts and narrative in their notebooks.

The footage from this video, according to the Wright University State Library, is from May 6, 1908 in France. (Note: the title of the video claims this is footage from the first flight. This is incorrect.)

The Wright Brothers and Photography

In Wilbur's 1908 speech, "Some Aeronautical Experiments," to a group of engineers in Chicago, Wilbur recounts the continuation of delight that photography offered. He shares:

In looking at this picture you will readily understand that the excitement of gliding experiments does not entirely cease with the breaking up of camp. In the photographic dark room at home we pass moments of as thrilling interest as any in the field, when the image begins to appear on the plate and it is yet an open question whether we have a picture of a flying machine or merely a patch of open sky.

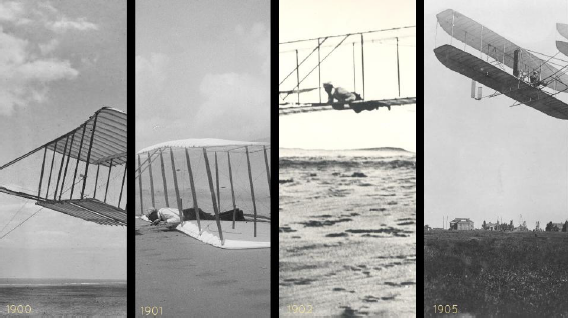

In addition to revealing the structural alterations made to the machines at yearly intervals, the images also capture the less obvious. When not in the field, the brothers could be found in their workshop as one might find scientists in a laboratory. In the early years, the time spent between visits to Kitty Hawk were crucial for responding to the successes and failures of their hands-on practice. The development of their machines shown in the photographs is the result of the time spent refining their previous efforts.

Wright Brothers' biographer, David McCullough, attributes the Wrights' recognition of the importance of photography to Otto Lilienthal's own tendency to document his flight experiments. News of the death of the German inventor in 1896 had sparked the brothers' interest in flight and they eagerly read any literature produced by Lilienthal. McCullough references an 1894 article in McClure's Magazine which includes Lilienthal in air donned in his bird-like equipment.

The Wright Brothers' Notebooks

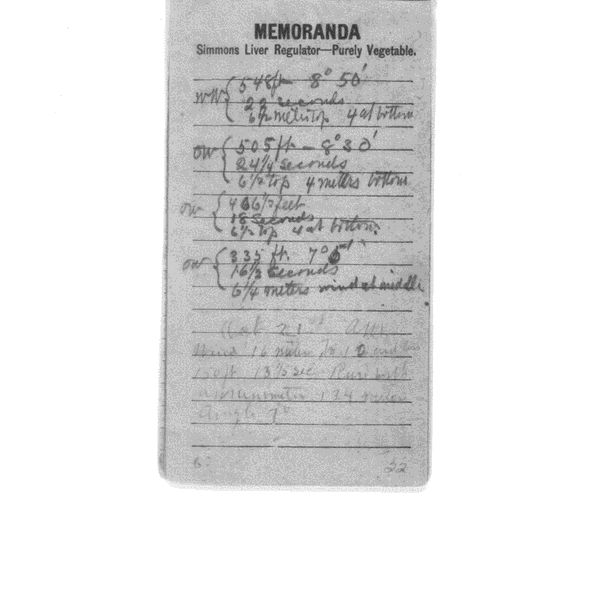

In addition to the photographs which serve as a visual record, thirty-one notebooks documenting the process in numbers and words are housed at the Library of Congress. Unsurprisingly, the notebooks were small enough for the brothers to be able to carry them in their pockets. Another interesting feature of their note-taking system is the segregation of information into different notebooks.

In the album below, we see three of Orville's notebooks used in 1902. It seems that he tended to divide them into three categories: photographs (as an organizational record regarding f-stop, date, subject, and where the images were located); data (regarding experiments); and narrative (day-to-day accounts and observations).

Wilbur also tended to separate his information into different notebooks. In the album below, we see three examples spanning different years, focusing mainly on data and narrative (it seems that Orville recorded the photography information). Captions provided below include excerpts from the journals.

Below is an example of Wilbur's notes that seem to be taken during trials done at in their Dayton, Ohio, workshop.

![Cover: [1902-1905] H 1902-3 WW](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5716a88ed210b8cd267f43a3/1495193319146-YZDVWLQNC016PIAF0T58/Wilbur+Wright+D-1902-05+cover.gif)

On December 17, 1903, Wilbur and Orville celebrated their first flight with a powered machine. The telegraph sent to their father and family read:

Success four flights Thursday morning all against twenty one mile wind started from level with engine power alone average speed through air thirty one miles longest 57 seconds inform press home for Christmas —Orevelle Wright

According to David McCullough, the telegram carried two mistakes: the longest flight time was 59 (not 57) seconds, and Orville's name is misspelled. The brothers took turns flying until, with the flyer landed, the machine caught a gust of wind and tumbled along the beach with one of the onlookers caught in the wires. He was uninjured. The brothers took the pieces of the flyer home and stored the plane back at home in Dayton, Ohio. Below is the photograph taken by onlooker John T. Daniels. Orville set up the camera and gave Daniels instructions to push the bulb the moment the machine was released from the railing.

The 1903 Flyer is stored at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

While the occasion was momentous, it was only the beginning. It served as confirmation of their efforts and encouraged them to continue to develop a machine that could sustain longer flight and land safely. In 1904, the brothers moved their testing site closer to home in Dayton, Ohio and continued their work. Their 1905 Flyer was considered their first practical flying machine.

Additional Resources

Part I of Wright Brothers: A Flying Idea offers a look into the Wright Brothers' early stages of investigation and preparation. The article connects to additional online resources not mentioned here. The links provided below (also mentioned in Part I) are cornerstones of the Wright online material.

Orville Wright's will stated that his executors could determine which institutes should receive the Wrights' papers. The Library of Congress was allowed to select certain works. They chose 100 printed items, 303 glass plate negatives of photographs, the Wright-Chanute correspondence, and some family correspondence. For access to these documents, visit the Digital Archives site containing the Wilbur and Orville Wright Papers.

The remaining documents were shared amongst family members. Over the years, many of the documents were bestowed upon the Wright State University Library to serve as the permanent repository for those documents. To view photographs and additional primary sources, visit their Special Collections and Archives.

For more details regarding Wilbur and Orville Wright's process of inventing the Flying Machine, visit the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

*Frontispiece

Page 30 of Subject File: Chanute, Octave—Photographs, Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, Originals, 1901; Library of Congress