Frida Kahlo: A Diary More Private than Portrait

"Who would say that marks and stains live and help to live?" —Frida Kahlo, Diary, page 47

A Gold-dusted Pain

“Despoiled of her clothes, showered by a broken packet of powdered gold carried by an artisan: will there ever be a more terrible and beautiful portrait of Frida than this one? Would she ever paint herself—or could she paint herself other than—as this “terrible beauty, changed utterly”? —Carlos Fuentes, Introduction to The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait

At thirteen years old, the artwork of Frida Kahlo would have primed me for anything I would later read about her. So two years later, when my aunt gave me as a gift Kahlo's biography (a hefty tome, and the first biography I ever read), there was no question that the chaos of the streetcar accident that broke Kahlo's body in so many ways also covered her in gold dust torn open from a craftsman's pouch. Whether myth or fact, the account of gold powder falling over the accident mirrors a theme that would persist throughout Kahlo's vast artistic output: art would forever be guilding to her pain.

Frida Kahlo's Diary: For Her Eyes Only

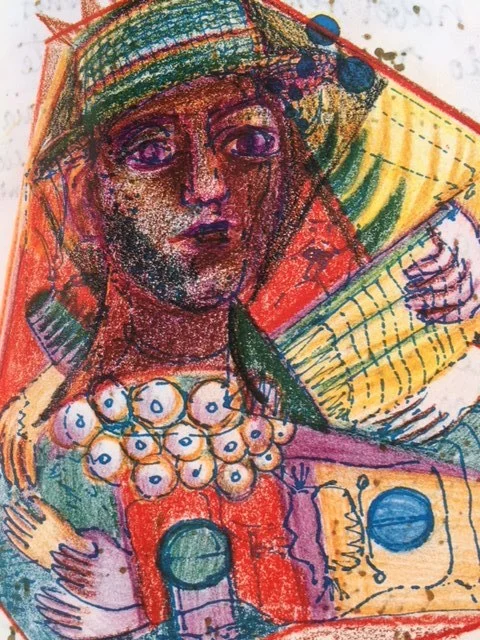

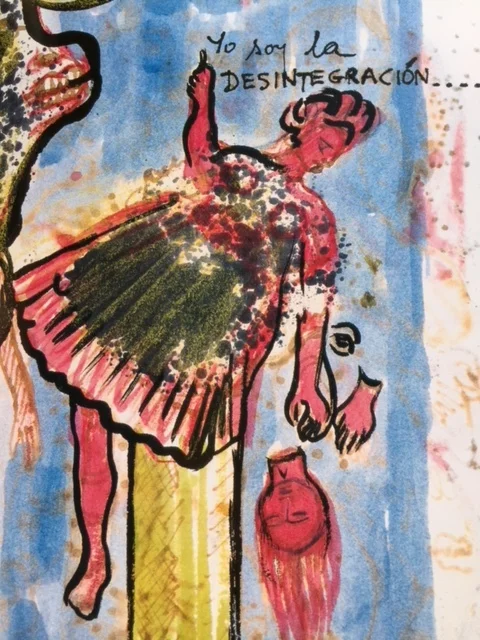

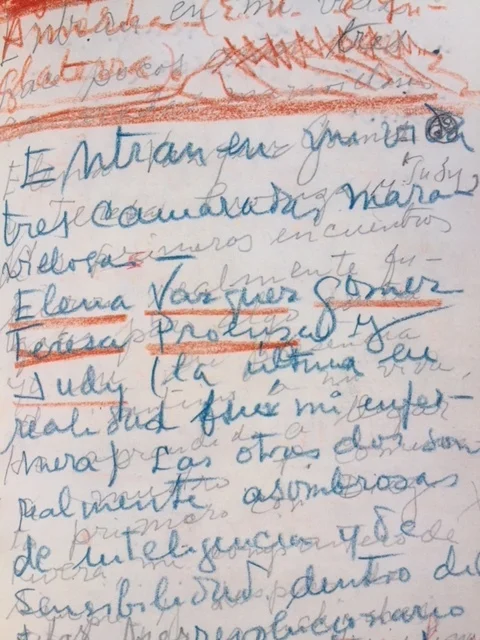

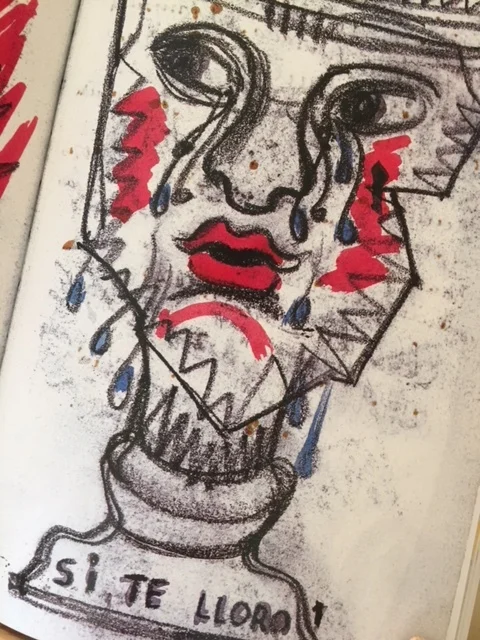

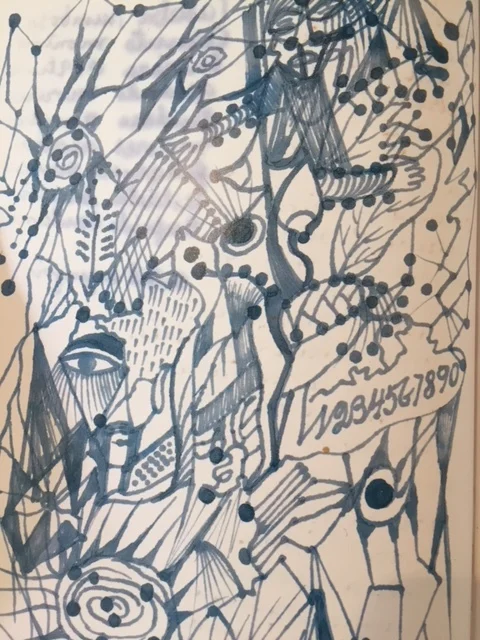

When Frida was about 36 years old, she began keeping a diary that would serve as another outlet for her emotional and artistic meditations. By this point in her life, she had already divorced and remarried Diego Rivera, her father had passed away some years earlier, and she had undergone a number of surgeries and miscarriages with still more to come. Her diary is filled with visual and textual "objects" that relay this pain: teardrops, discombobulated bodies (with particular emphasis on feet and legs), lists, songs, letters, and fragments all riddled with sources of suffering.

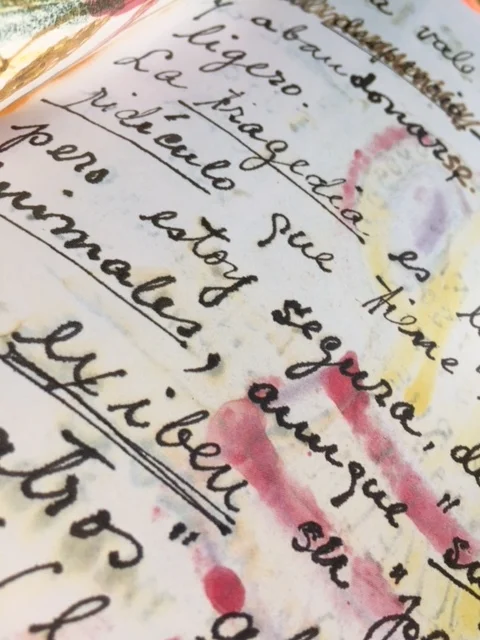

As with so much of Kahlo's art, there are always many dimensions. The diary tracks brighter angles, too. For example, "It is strength to laugh and lose oneself, to be [crossed out: "cruel and"] light," and her solace in nature: "morning breaks, the friendly reds, the big blues, hands full of leaves, noisy birds..."

Diary, Not Sketchbook

Regardless of the many drawings that appear in the diary, it would seem that Kahlo did not necessarily approach the book as a sketchbook. In the essay that accompanies the publication of the diary, Sarah M. Lowe makes the point that none of the drawings resemble an artist working on preparatory sketches or figuring out solutions related to her paintings. The prolific Mexican author Carlos Fuentes distinguishes between Kahlo's choice of when to paint and when to write:

The Diary is her lifeline to the world. When she saw herself, she painted and she painted because she was alone and she was the subject she knew best. But when she saw the world, she wrote, paradoxically, her Diary, a painted Diary which makes us realize that no matter how interior her work was, it was always uncannily close to the proximate, material world of animals, fruits, plants, earths, skies.

It is an interesting question to consider. Which distinctions, if any, can be made when considering what might have compelled Kahlo to paint or, instead, turn to her diary?

Visual/Textual/Personal/Private

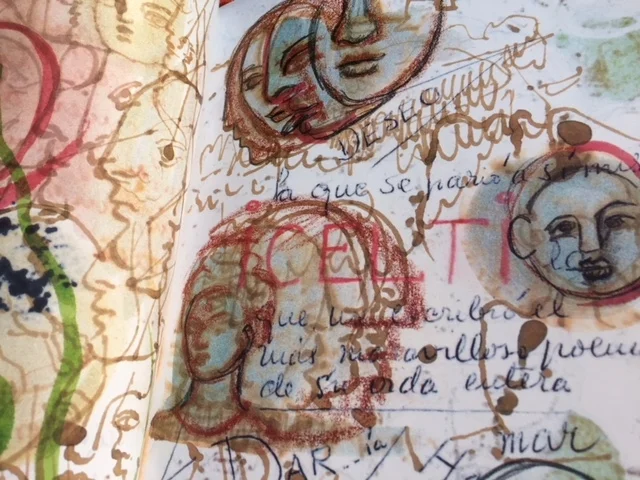

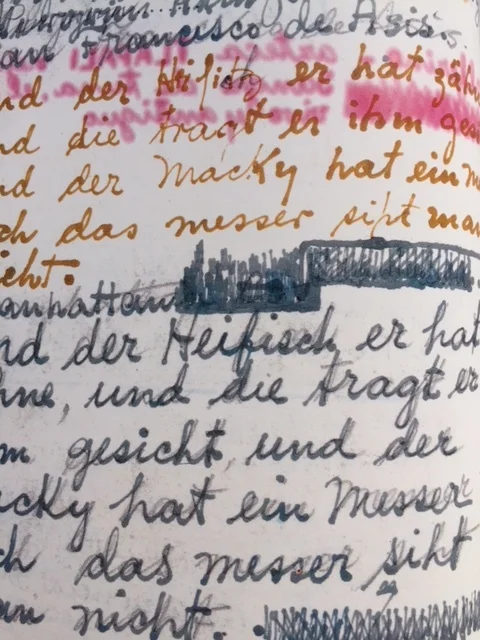

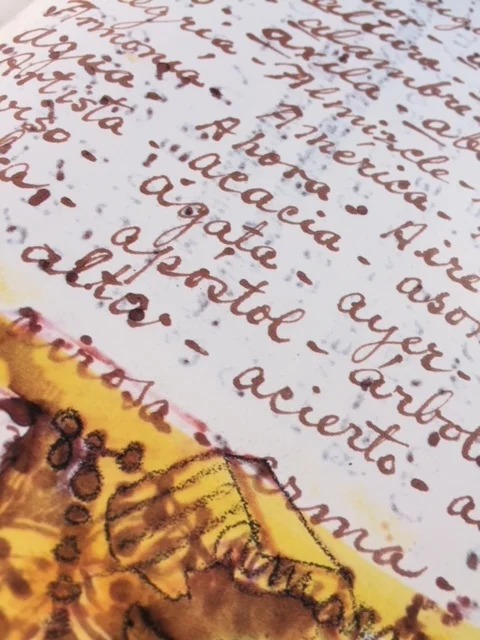

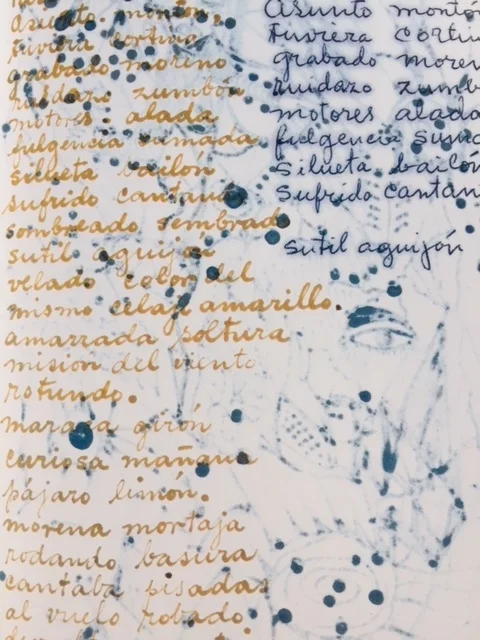

The pages carry an impasto-like quality in the layers of text, scratch-outs, and drawings. Verso appears through recto: splotches and writing seep through the page adding to the sense of all-consuming anguish.

Below: Two drawings side by side. On the left, the caption reads "Don't come crying to me!" On the right, it responds, "Yes, I cry to you!"

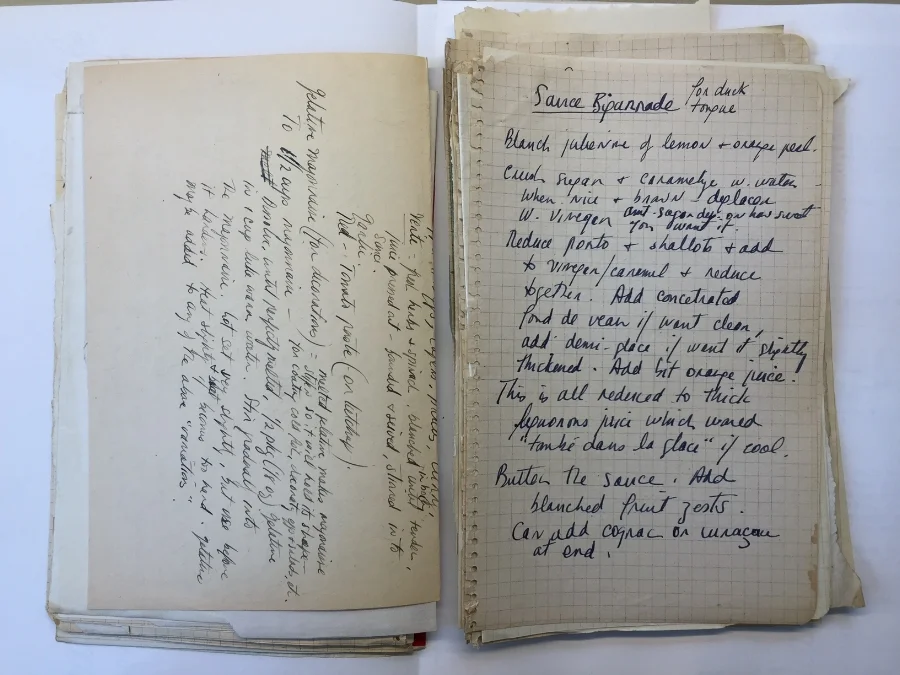

Below: The writing on the left is the second page of a letter written to Diego Rivera in her diary; it reveals ink marks from the drawing she creates on the back of the paper.

*All images from The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait

Additional Resources

The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait includes a compelling introduction by Carlos Fuentes. In his essay, he relates Kahlo herself to grand dames such as Cleopatra, Coatlicue, and Tlazolteotl; he compares the scope of her life to the political history of Mexico following the revolution; and, he places her art amongst the bittersweetness of magical realism, that poignant genre of (political) reality buried in fantasy.

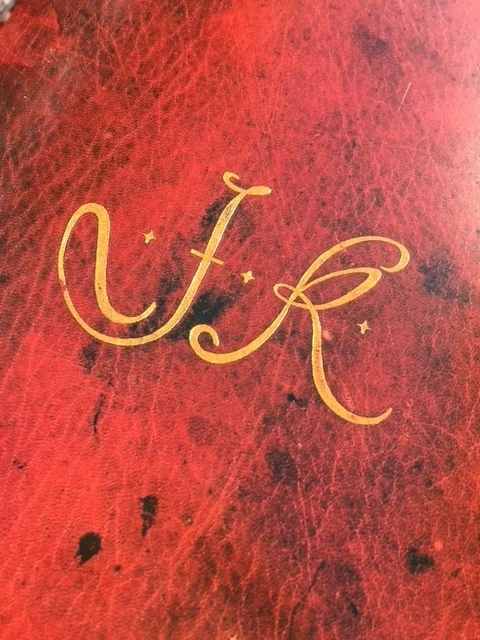

*Frontispiece

By Frida Kahlo from The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait (2005). Edited by Carlos Fuentes and Sarah M. Lowe. New York: Abrams and La Vaca Independiente S.A. de C.V.