Virginia Woolf: A Room of One's Own

"But what is the state of mind that is most propitious to the act of creation, I asked? Can one come by any notion of the state that furthers and makes possible that strange activity?" —Virginia Woolf, A Room of One's Own

What does make a mind "most propitious to the act of creation?" In many ways, Noble Oceans is in pursuit of an answer to the same question. This quest to highlight the processes of bringing an idea to life proceeds from the premise that it is not necessarily genius that should receive the credit for great creations. Rather, here we look to the habits and methods that structure such labor: evidence of the moments when the masterful converges with the mundane.

Dogs Will Bark

In Virginia Woolf's extended essay A Room of One's Own, Woolf approaches the mundane as a counteractive agent on the interior workings of the mind. She writes:

And one gathers from this enormous modern literature of confession and self-analysis that to write a work of genius is almost always a feat of prodigious difficulty. Everything is against the likelihood that it will come from the writer's mind whole and entire. Generally material circumstances are against. Dogs will bark; people will interrupt; money must be made; health will break down.

For Woolf, the extent to which mundanity is harmful to the willing and eager mind is a matter of the degree to which the forces of oppression permeate daily life for some over others. A Room of One's Own is a study into how the prejudices held against women have kept them from opportunities of education, and more specifically, from pursuing their own creative endeavors.

Granted, she recognizes that the daily workings of the world are generally inhospitable to the act of writing for anyone:

Further, accentuating all these difficulties and making them harder to bear is the world's notorious indifference. It does not ask people to write poems and novels and histories; it does not need them.

But she is more interested in the question of why, over centuries, the daily workings of the world have barred the existence of women creatives:

The indifference of the world which Keats and Flaubert and other men of genius have found so hard to bear was in her case not indifference but hostility. The world did not say to her as it said to them, Write if you choose; it makes no difference to me. The world said with a guffaw, Write? What's the good of your writing?

In analyzing the question, early on Woolf presents a structural remedy for the female writer: "a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction." A room of one's own would serve as a barrier between the solitary act of writing and the demands of a world designed to hinder such independence.

A Room of Her Own

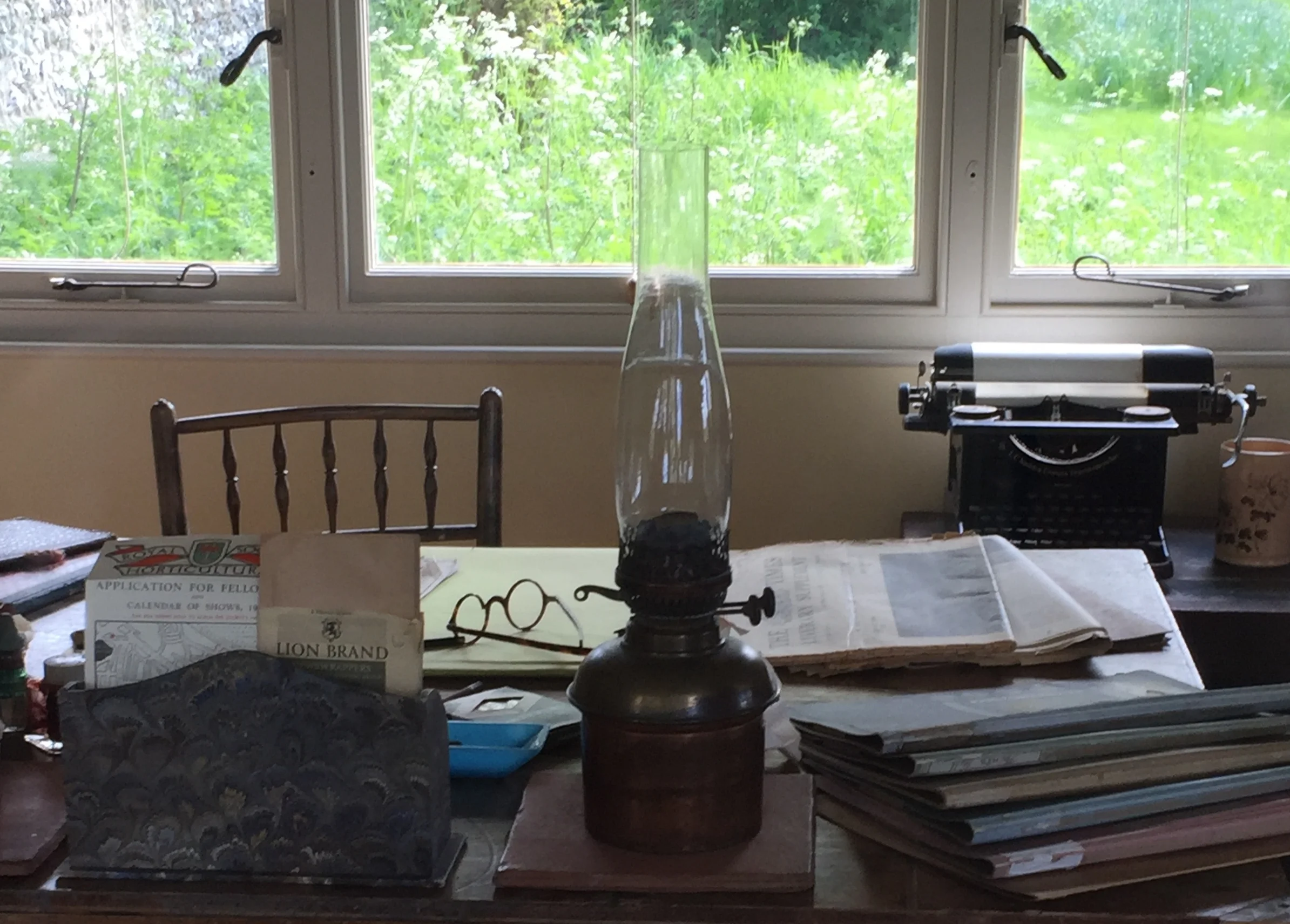

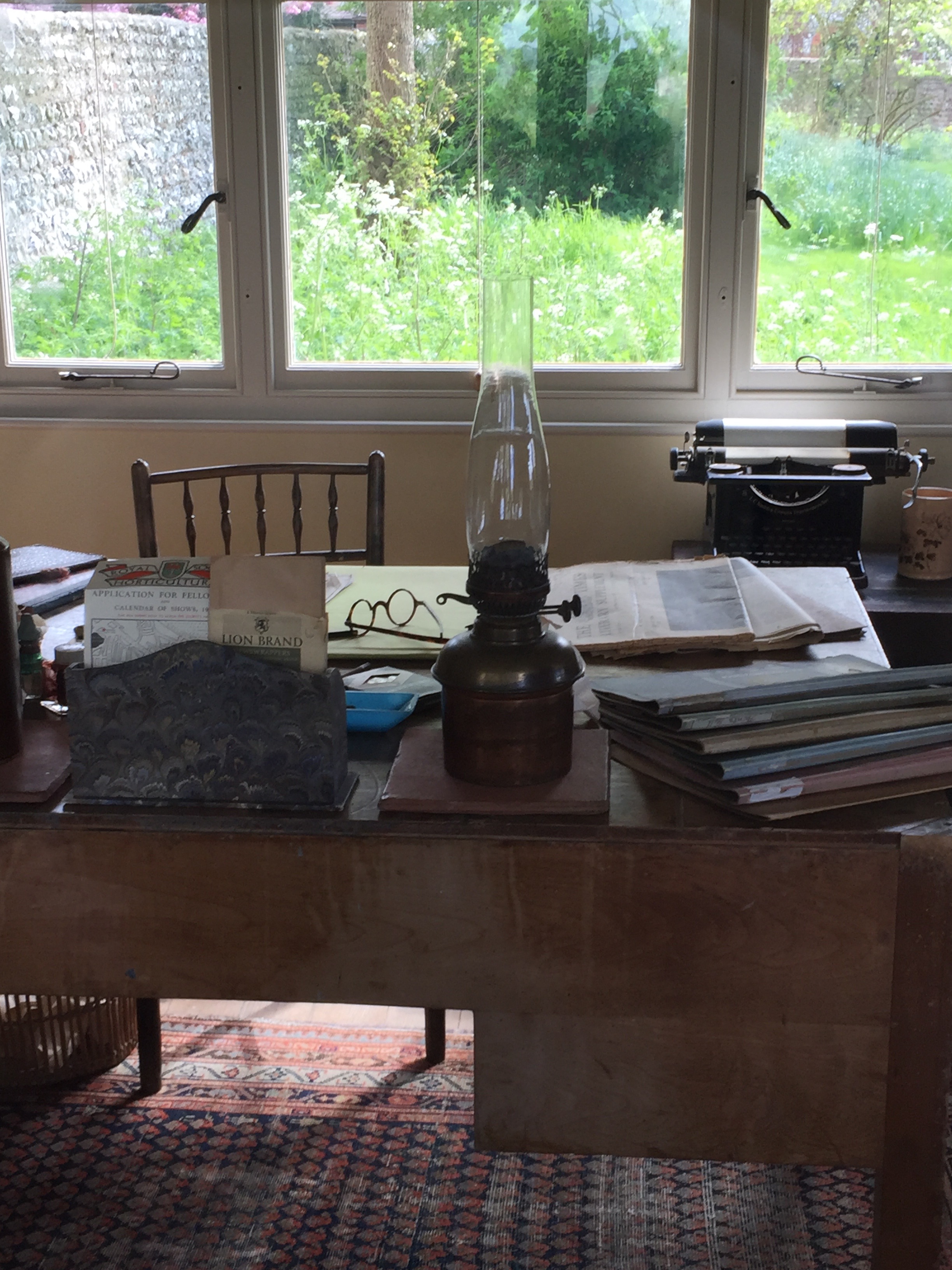

Woolf must have benefitted from having a room of her own. The writing lodge, as it was called, was built in 1934 after a bit of shuffling of rooms over the previous ten years at the main house. The original structure of the house can be seen to the left of the tree; her desk faced the white doors and patio. To the right of the tree, an addition was made years later for Angelica Garnett, Woolf's niece.

While it was a place of solitude, the patio also served as a convening point for many of the guests at Monk's House. The image below sets the lodge within its own time, reminding us that even work must settle into the rhythm of daily life:

In Downhill All the Way: An Autobiography of the Years 1919-1939, Woolf's husband, Leonard, describes Virginia Woolf's disciplined approach as she walked to the writing lodge "with the daily regularity of a stockbroker." From the following lines from her 1929-1931 letters, we can envision Woolf preparing herself for the coming day:

[I] shall smell a red rose; shall gently surge across the lawn (I move as if I carried a basket of eggs on my head) light a cigarette, take my writing board on my knee; and let myself down, like a diver, very cautiously into the last sentence I wrote yesterday.

And so she went forth into the noble ocean of her mind.

Additional Resources

For access to a first edition copy of A Room of One's Own and a letter from Virginia Woolf to the poet Frances Cornford regarding the essay, visit Professor Rachel Bowlby's article at the British Museum Library Archives. The article, "An Introduction to A Room of One's Own," provides greater background on the essay as a key work of feminist criticism.

The 2005 Harcourt, Inc. edition of A Room of One's Own provides an annotated version of Woolf's essay.

*Frontispiece

Virginia Woolf's desk in the Writing Lodge at Monk's House