Emily Dickinson: Poetic Gesture

“I’ll never forget the shock of opening the second edition of her poems in which the dashes had been restored—the dashes and the capitalizations had been restored—and getting a sense of [a] whole new reading of this poetry, a whole new voice. Much more jagged, much more personal, much more original, much more uncontainable than I had ever thought her to be." —Adrienne Rich, 1988, recording from The Kitchen Sisters podcast, “Black Cake, Emily Dickinson’s Hidden Kitchen

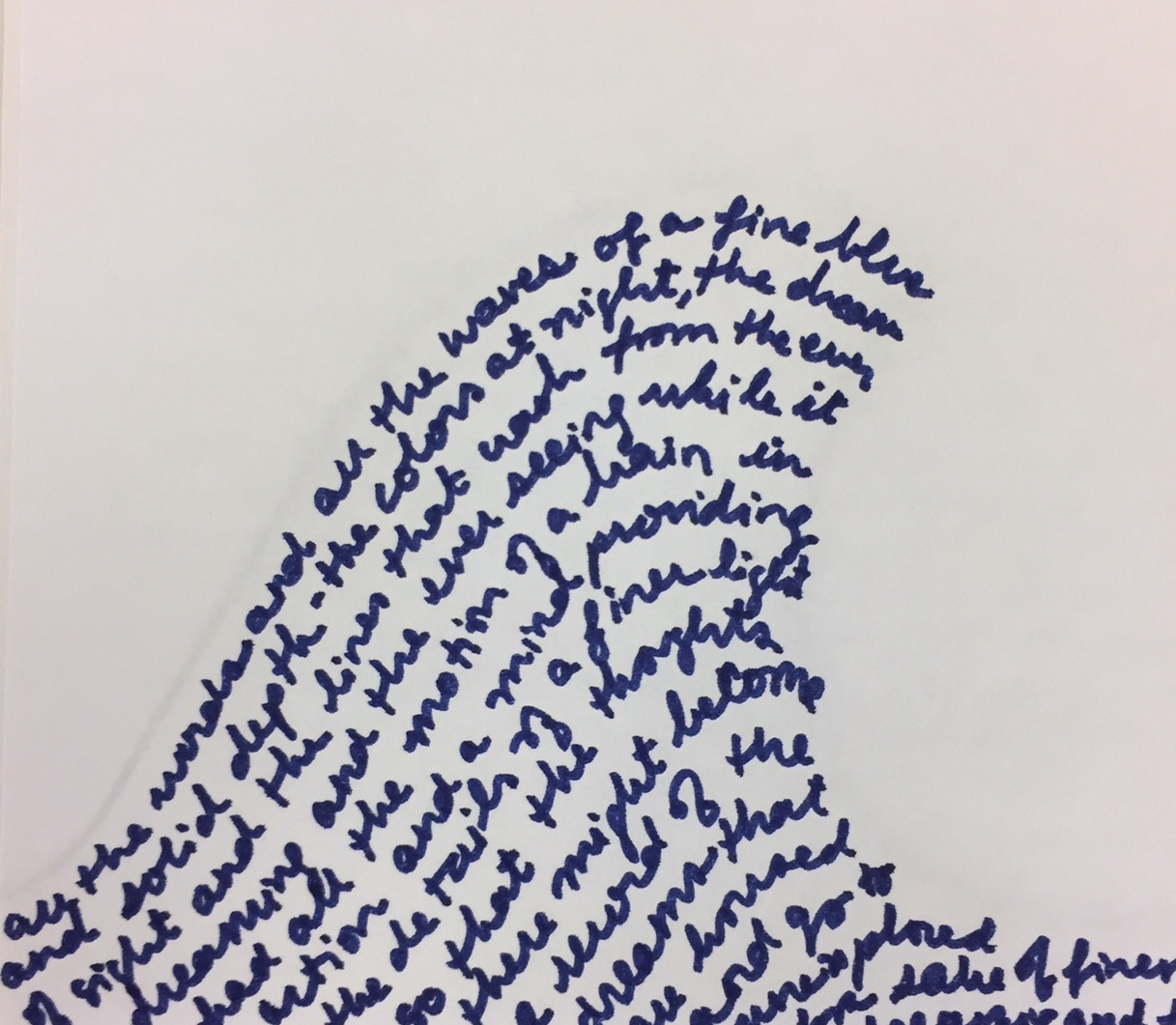

Poetic Gesture

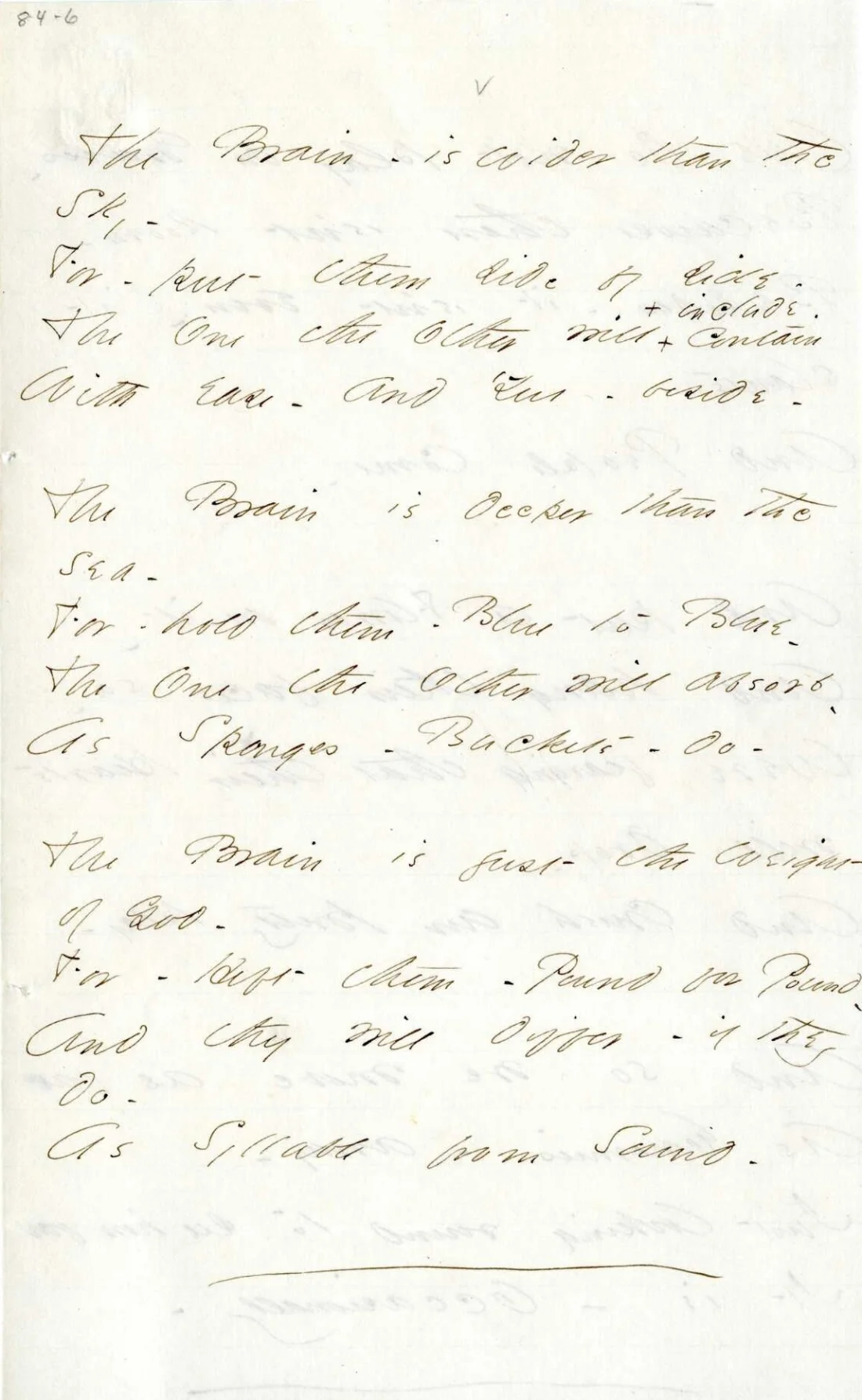

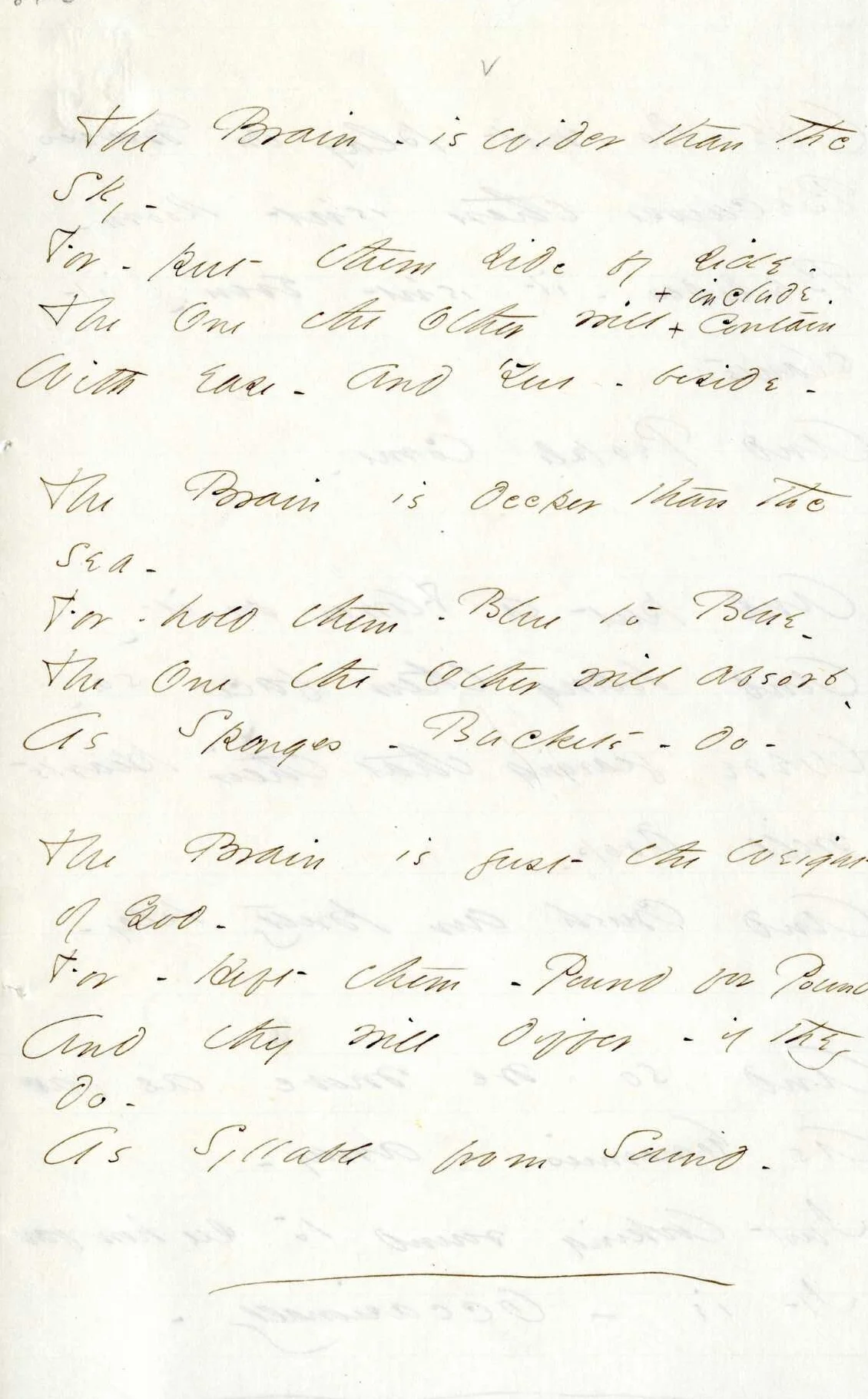

To read Emily Dickinson’s handwritten poems is to interpret them with other senses. Visually, they add a layer of the poet’s pensive depth. Plus signs serve as footnotes signaling alternative phrasings. Bold x’s cross out possible word choices, while underlining seems to suggest final decisions. In the handwritten form, her choice of capitalization is magnified by the large loops and exaggerated curves of her letters, something not quite portrayable by the regimented typescript. Her manuscripts are bespotted by dashes of varying lengths and positionings as they sit next to the words.

While there are many editions of Dickinson's published work, there is nothing quite so intimate as reading them in her own script. To read her poetry through the history of the published editions of her work, however, is to read through a history that was making sense of a (woman) poet far more contemporary than her own era could accommodate.

Image provided courtesy of the Amherst College, Amherst, MA at the Emily Dickinson Archive

Origins: Personal Publication

For a poet who wrote nearly 1,800 poems, only ten were published in her lifetime. Scholars are not sure that Dickinson authorized their publication. Upon her death, her younger sister, Lavinia, found hundreds of Dickinson’s poems in her bedroom dresser drawer. In what is perhaps a form of self-publication, many of them were bound as booklets, now called fascicles. These fascicles were later separated by her first editors who organized the poems in what they considered to be a more "appropriate" order.

Others did read her poetry in her lifetime, however. In letters to friends and family she would enclose poems. Sometimes, different variations of the same poem—a change of a word or two—would be sent to different people.

Posthumous Publication

In the introduction to The Gorgeous Nothings (2012), editor Jen Bervin relays some of the traditional difficulties of publishing Dickinson's work. She quotes Jerome McGann, author of Black Riders: The Visible Language of Modernism:

'Dickinson's scripts cannot be read as if they were "printer's copy" manuscripts, or as if they were composed with an eye toward some state beyond their handcrafted textual condition.' He continues, 'Emily Dickinson's poetry was not written for a print medium, even though it was written in an age of print. When we come to edit her work for bookish presentation, therefore, we must accommodate our typographical conventions to her work, not the other way around.'

By following the various publications of Dickinson's poetry, we trace her work through the manifestations of print translations.

Early Publication

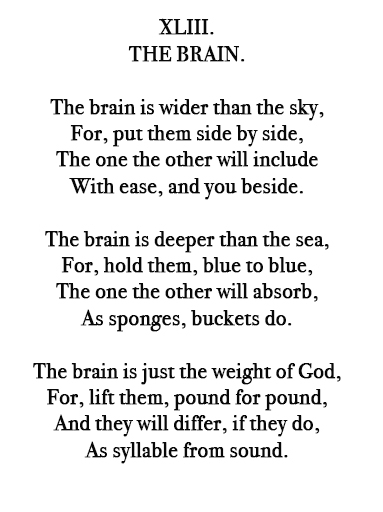

The early publications of Dickinson’s poems in the late 1890s and early 1900s were under the heavy editorial hands of Mabel Loomis Todd and Thomas W. Higginson. Often portrayed as brutish editors with no regard for Dickinson's original intention, it would seem they were quite aware of Dickinson's admirable uniqueness. In the Preface to the publication of Dickinson's Poems: Second Series (1891), Mabel Loomis Todd writes:

In Emily Dickinson's exacting hands, the especial, intrinsic fitness of a particular order of words might not be sacrificed to anything virtually extrinsic; and her verses all show a strange cadence of inner rhythmical music. Lines are always daringly constructed, and the "thought-rhyme" appears frequently,—appealing, indeed, to an unrecognized sense more elusive than hearing.

Loomis Todd compares Dickinson to other revolutionary creations, essentially categorizing her work as a new genre:

Like impressionist pictures, or Wagner's rugged music, the very absence of conventional form challenges attention.

As it would seem, Loomis Todd and Higginson faced the same challenges that editors today still face when conveying Dickinson's work into print. Loomis Todd explains that Dickinson's "perplexing footnotes" and multiple word choices "have at times thrown a good deal of responsibility upon her Editors." The criticism that these two editors tend to face from a modern perspective is that their pruning portrayed a poet in much more conventional terms, compromising Dickinson's uniqueness (no one altered or edited one of Renoir or Monet's paintings).

Mid-Century Publication

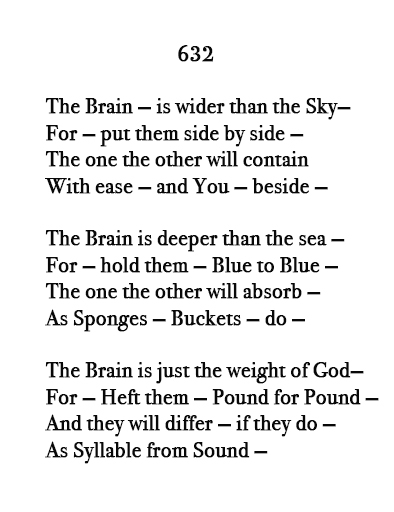

When ownership of Dickinson’s papers was transferred to Harvard, editor Thomas Johnson had access to the full 1775 poems and fragments that made up Dickinson’s manuscripts. In 1955 he published 3 volumes of The Poems of Emily Dickinson. He explains his editorial choices in the Introduction to the 1970 version of The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson:

Selection becomes mandatory for the semifinal drafts. Though by far the largest number of packet copies exist in but a single fair-copy version, several exist in semifinal form: those for which marginally the poet suggested an alternate reading for one word or more. In order to keep editorial construction to a bare minimum, I have followed the policy of adopting such suggestions only when they are underlined, presumably Emily Dickinson’s method of indicating her own preference.

He goes on to explain:

I have silently corrected obvious misspellings (witheld, visiter, etc.), and misplaced apostrophes (does’nt). Punctuation and capitalization remain unaltered. Dickinson used dashes as a musical device, and though some may be elongated end stops, any “correction” would be gratuitous. Capitalization, though often capricious, is likewise untouched.

Compare, for example, Dickinson’s handwritten version of "The Brain—is wider than the Sky—" to Todd's version in Poems: Third Series (1896) and Johnson's 1955 version.

Current-day Publication

Today, publications sway heavily towards preserving as much of Dickinson's written gestures and word choice as possible. The fidelity to her original work suggests that, in these modern times, we are much more open to the multiplicity of her intention. Publications such as Emily Dickinson's Poems: As She Preserved Them by Cristanne Miller attempt to translate the fascicles through print by including alternative phrasings in the margins or in footnotes, and by means of italicization and brackets as replacements for underlining, plus signs, and other word choice.

Other editions have attempted to recreate the order of poems as they might have been bound in Dickinson's fascicles. Emily Dickinson's Fascicles: Method and Meaning by Dorothy Huff Oberhaus and Reading Fascicles of Emily Dickinson: Dwelling in Possibilities by Eleanor Heginbotham are two examples of this type.

Additional Resources

For direct links to Emily Dickinson’s manuscripts, visit the Emily Dickinson Archive.Visit the Emily Dickinson Museum for an array of resources about Dickinson’s life and work.

Today, both Thomas Johnson The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson (1955) and the more recent R.W. Franklin's The Poems of Emily Dickinson (1998) are considered the most comprehensive editions available. Some variations exist between the two as the two authors disagreed on certain word choices and the chronology of poems. For details between the two editions, visit the Emily Dickinson Archive's Frequently Asked Questions.

*Frontispiece

Emily Dickinson's "The brain is wider than the" circa 1862 [date assigned by Thomas H. Johnson]; courtesy of Emily Dickinson Archive under Creative Commons license