Jane Austen: Plan of a Novel

"Writers not only reveal themselves in their choice of materials, they also reveal themselves in the way they use their materials." —Professor Kathryn Sutherland, Jane Austen scholar

The Written Gesture of Thought

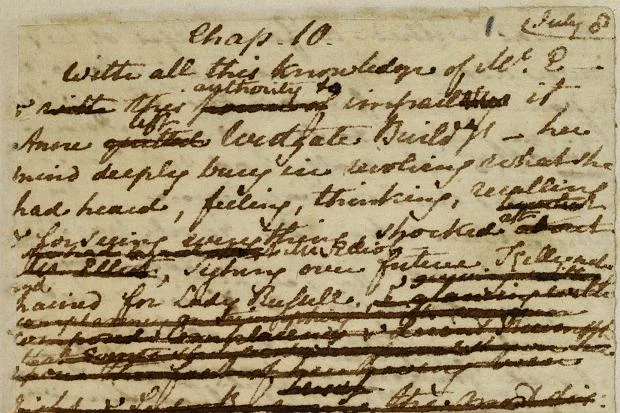

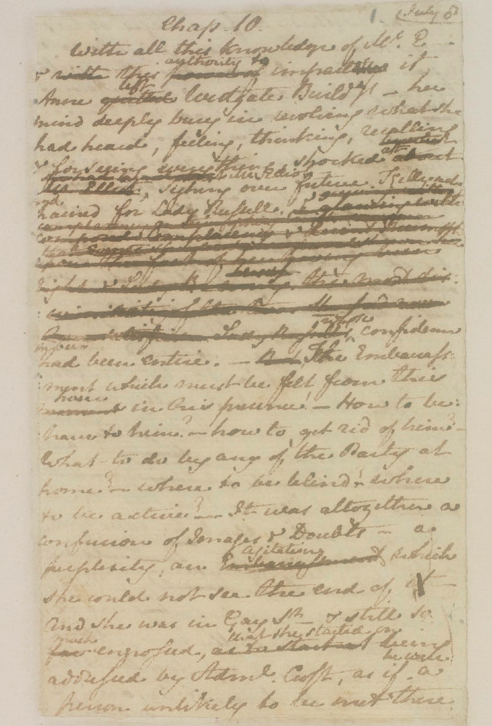

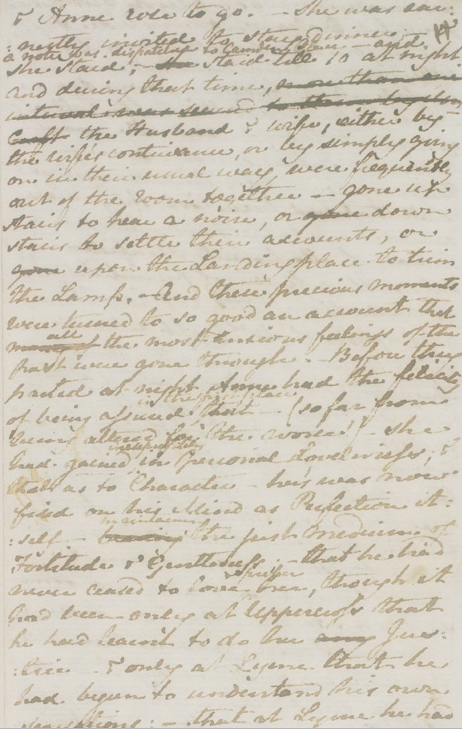

In becoming familiar with the manuscripts of authors, one begins to realize that the gestural marks of handwriting, punctuation, and spatial configuration reveal a certain movement of thought. Such movement might be distinguished from the substance of thought found in the words themselves.

In the short video, "Jane Austen's Manuscripts," Professor Kathryn Sutherland analyzes the chirographic marks as visual indicators of the thinking process.

She compares areas of little to no revision to those areas where heavier revisions are made. As she points out, patterns emerge: dialogue largely remains unaltered compared to scenes between dialogues. Professor Sutherland describes:

One of the things that you see time and time again, is that when she reaches a point where the characters are in conversation, her hand runs smoothly—often without a pause, often without a mistake, often without a slip or correction.

The observation is significant not because it reveals an importance of "flawless" execution. Rather, it highlights the pockets of clarity, those moments when thought flows swiftly rather than staggering its way onto paper.

Plan of a Novel

A striking variety of Austen manuscripts exist which provide insight into Austen's development as the "conversational novelist." Three volumes of juvenilia and a number of unfinished novels provide a record of Austen's work at different stages of her life—from her teenage years to the year of her death (age 41). What is missing, however, are any complete manuscripts of her published novels. This fact has led scholars to suspect that Austen may have discarded the drafts once she completed the novels.

As there is no concrete evidence for Austen's methods of preparation, we are left to speculate. One document, Plan of a Novel, according to hints from various quarters, might serve as a hint to her regular methods. The document itself is a satire, a joke even, so we must tread carefully in considering its value as a clue to her preparatory methods. Austen writes the piece as a response to the Prince Regent's librarian, James Stanier Clarke's, recommendation for Austen's next storyline. When Austen writes of one of her characters, Mr. Gifford, "He, the most excellent Man that can be imagined, perfect in Character, Temper &Manners..." she is poking fun at Clarke's suggestions for the novel. In an editorial note from Austen-Leigh's Memoirs of Jane Austen (see link below), Professor Sutherland explains that "most of the suggestions incorporated verbatim from Clarke's hilariously self-preening letters."

Aside from the content itself though, what if the method we see here—with descriptions of the characters and a constellation of events broadly written—offers a window into the way Austen prepared her other novels? We cannot know for sure, as Austen had no intention of publishing Clarke's recommendation; this may have simply served as a structure for collecting the various contributions to a sustained "inside joke" from friends and family (the names in the margins correspond to their respective contributions to the storyline). A full transcript to the four-page document is provided at Jane Austen's Fiction Manuscripts: A Digital Edition, edited by Kathryn Sutherland (2010)*. The original document is archived at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York.

The Repetition of Revisal

The format of the document itself, if used with other novels, might have allowed Jane to map out a large sketch of whatever novel she had in mind. In The Real Jane Austen, biographer Paula Byrne relies on an account from Austen's older sister, Cassandra, to try to piece together Austen's writing methods:

The interesting thing about Cassandra’s description of the plot of the novel, recorded many years later, is what it reveals about her sister’s compositional method: Jane Austen sketched out the entire plot of the novel first. She knew from the beginning how each of her novels was going to end.

Her brother, Henry, also elaborated upon Austen's compositional methods. Byrne's provides commentary to Henry's description:

Henry Austen, who knew her books better than anyone apart from Cassandra, commented on her compositional methods: ‘For though in composition she was equally rapid and correct, yet an invincible distrust of her own judgment induced her to withhold her works from the public, till time and many perusals had satisfied her than the charm of recent composition was dissolved.’ This is absolutely right with regard to the ‘time and many perusals’ his sister devoted to her drafts, but perhaps wrong in the phrase ‘invincible distrust of her own judgement’: it was rather that she trusted the considered judgement that came with rewriting.

As Byrnes puts it, "Jane Austen was a worker. She revised and improved and honed."

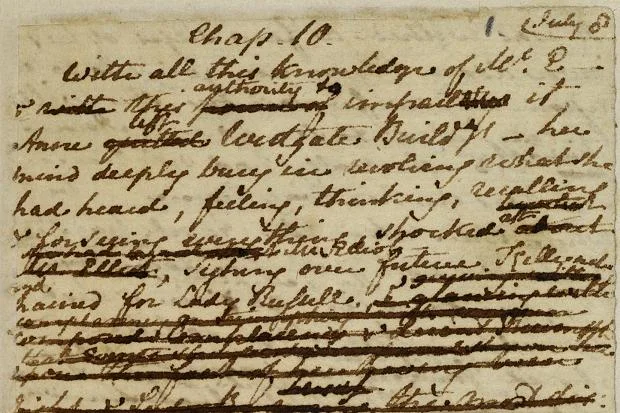

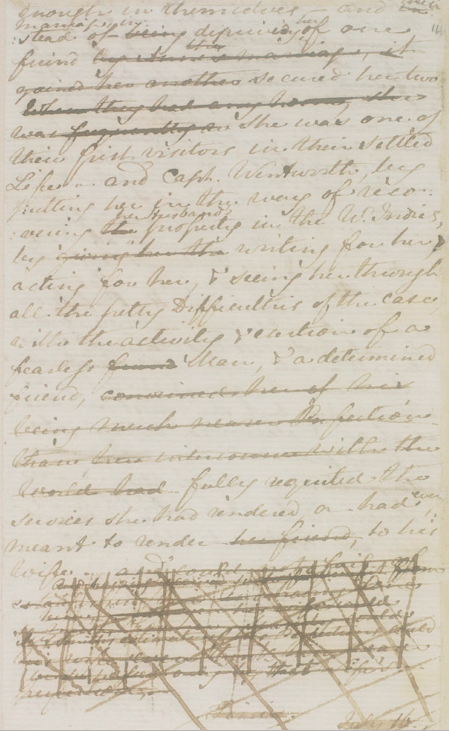

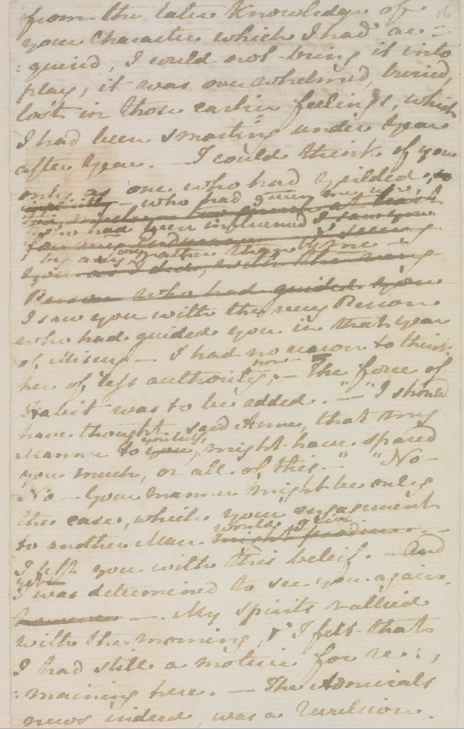

Such revising is best captured by the only surviving manuscript that exists for any of Austen's completed novels. The following document, archived by the British Library, reveals the revisions Austen made to the ending of Persuasion. Many modern copies of the novel include the original ending in the appendix.

An audio recording of the cancelled final chapter is provided by the British Library:

Additional Resources

For access to primary accounts from family members, consider reading James Edward Austen-Leigh's A Memoir of Jane Austen. The book was first published in 1870 by Austen's nephew and later released in 1871 to include additional manuscripts (including "Lady Susan," "The Watsons," and the cancelled chapters of Persuasion). The Oxford World Classics edition compiles additional family recollections, including those written by Austen's brother Henry in 1833, and her nieces, Anna Lefroy (pub. 1864) and Caroline Austen (pub. 1867). The edition includes an introduction by Professor Kathryn Sutherland, placing the memoirs of Austen as part of a larger context of the family's stakes in controlling the narrative surrounding Austen's (and thereby, the family's) biographical accounts.

Paula Byrne's The Real Jane Austen: A Life in Small Things structures many of the accounts and letters available in Austen-Leigh's A Memoir of Jane Austen around eighteen objects that "[conjure] up a key moment or theme in Austen's life and work."

Plan of a Novel

The full citation for the Plan of a Novel transcript is: Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts: A Digital Edition, edited by Kathryn Sutherland (2010). Available at http://www.janeausten.ac.uk. ISBN: 978-0-9565793-1-7

*Frontispiece

Jane Austen's Manuscript of chapters 10 and 11 of Persuasion: 8-18, July 1816; British Library