Virginia Woolf: The Hours Become Mrs. Dalloway

"Saturday, August 20, 1923: I’ve been battling for ever so long with The Hours, which is proving one of my most tantalising and refractory of books. Parts are so bad, parts so good; I’m much interested; can’t stop making it up yet—yet.” —Virginia Woolf, from A Writer's Diary

The Manuscript

Novels in their finished form convey a sense of finality. With their bound and beautiful covers, the numbered pages and steady lines of text, there is a promise of completion. The ideas that live inside the text seem as though they could not have been written in any other way. Each decision made by the author is fossilized within the pages.

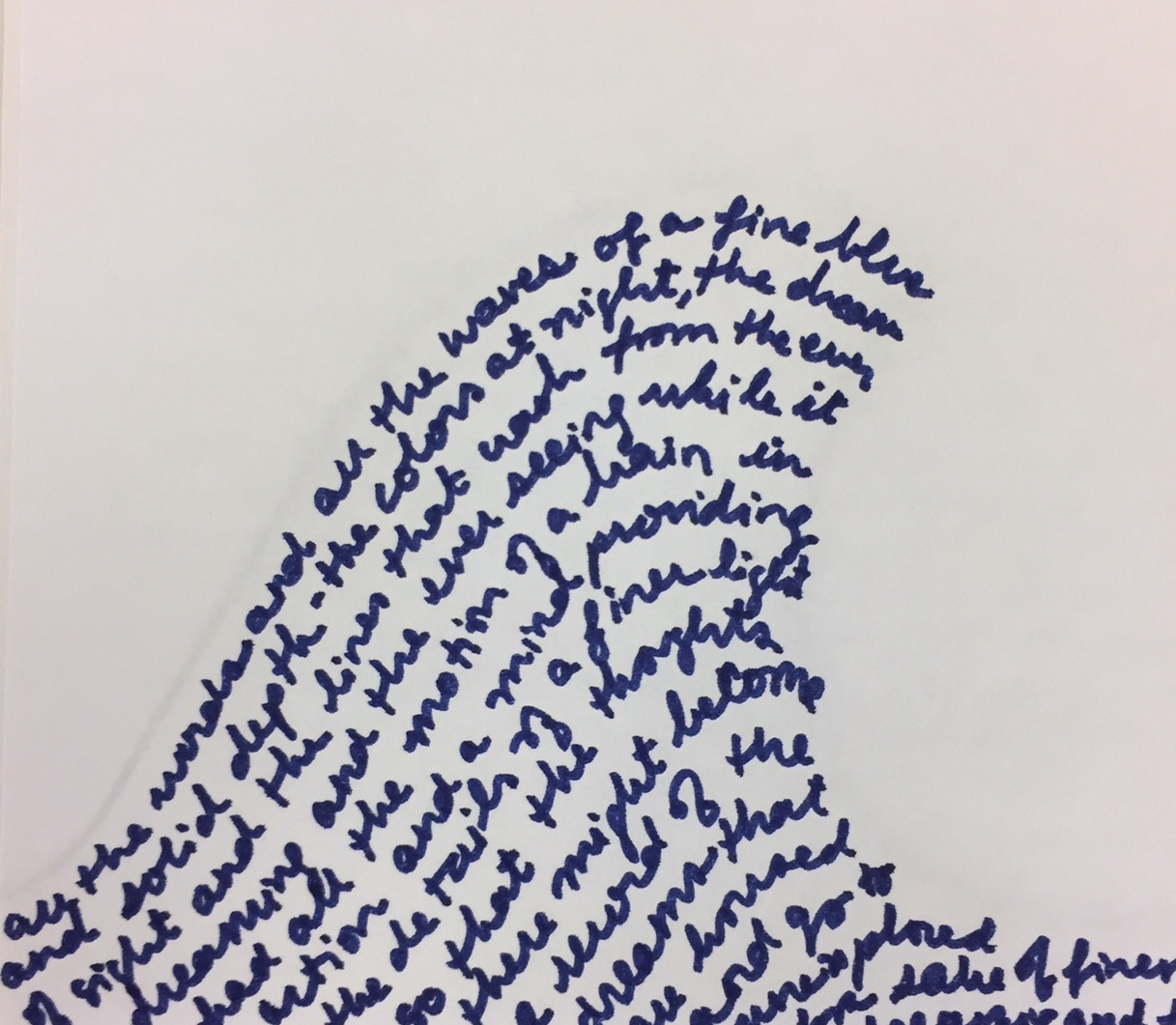

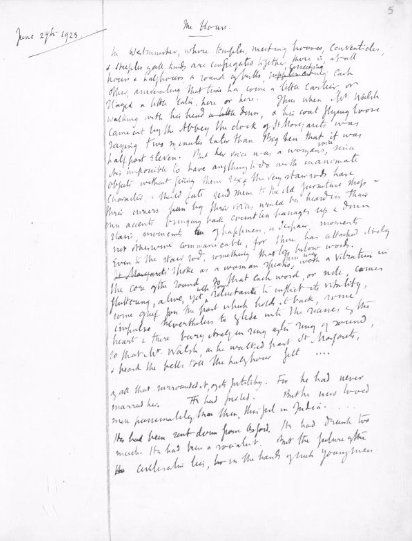

This is why manuscripts in their messiest form offer a liberated view of how ideas are culled into existence. The scratch-outs, the scrawl, the notes in the margins: all of these point to the dynamic process of thinking.

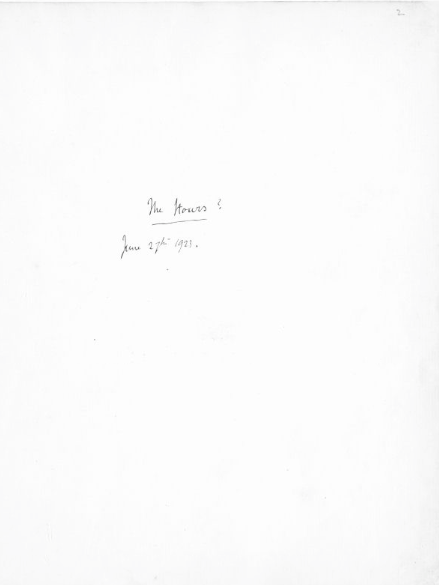

Consider Virginia Woolf’s handwritten drafts for The Hours/Mrs. Dalloway (Woolf oscillated between the titles before deciding on Mrs. Dalloway). From the drafts, one can appreciate Woolf’s search for le mot juste, the right words and phrasing. The margins allow her to draw attention to notes and alternatives.

Ideas into Words

"Wednesday, August 16th, 1922: For my own part I am laboriously dredging my mind for Mrs. Dalloway and bringing up light buckets. I don't like the feeling." —Virginia Woolf, from A Writer's Diary

Woolf's diary was a place where she could freely articulate her frustrations and doubts about the writing process. In A Writer’s Diary: Being Extracts from the Diary of Virginia Woolf, we can see how Woolf sorted out her thoughts as she prepared to write the novel:

Tuesday, June 19, 1923

But now what do I feel about my writing?—this book, that is, The Hours, if that’s its name? One must write from deep feeling, said Dostoievsky. And do I? Or do I fabricate with words, loving them as I do? No, I think not. In this book I have almost too many ideas. I want to give life and death, sanity and insanity; I want to criticise the social system, and to show it at work, at its most intense.

The stage of creation when an idea is still largely in the mind (and not yet on paper) can be a time of both hopeful promise and utter anguish. When ideas are not yet subjected to the dimensionality of creation—the dutiful linearity of sentences, the order of grammar, the specificity of words—they can remain both everything and nothing.

After nearly a year of contemplating her novel and writing bits and pieces here and there, one week after her June 19th diary entry she began setting out the first lines of her novel.

Words into Ideas

Woolf began thinking about her work for Mrs. Dalloway upon completing Jacob’s Room, but the idea for the novel stemmed from one of her short stories, “Mrs. Dalloway in Bond Street.” In a diary entry, she writes:

Saturday, October 14, 1922:

Mrs. Dalloway has branched into a book; and I adumbrate here a study of insanity and suicide; the world seen by the sane and the insane side by side—something like that. Septimus Smith? is [sic] that a good name? and [sic] to be more close to the fact than Jacob: but I think Jacob was a necessary step for me, in working free.

Woolf's previous novels provided her with an awareness of how she wanted to shape her upcoming novel:

Sunday, October 29, 1922

I want to think out Mrs. Dalloway. I want to foresee this book better than the others and get the utmost out of it. I expect I could have screwed Jacob up tighter, if I had foreseen; but I had to make my path as I went.

Reaching the End

There came a time when Woolf was finally finishing her novel. On Sunday, September 7, 1924, she grew closer to writing her vision for the ending:

Now I do think this might be the best of my endings and come off, perhaps. But I still have to read the first chapters, and confess to dreading the madness rather; and being clever. However, I'm sure I've now got to work with my pick at my seam, if only because my metaphors come free, as they do here. Suppose one can keep the quality of a sketch in a finished and composed work? That is my endeavor. Anyhow, none can help and none can hinder me any more.

Sometime around late October she finished her novel. By December 13th, 1924 she was tidying up the final work:

I am now galloping over Mrs. Dalloway, re-typing it entirely from the start, which is more or less what I did with the V.O. [The Voyage Out, 1915]: a good method, I believe, as thus one works with a wet brush over the whole, and joins parts separately composed and gone dry.

To have worked so hard and reach the end—with all the fluctuations of clarity that went with the effort—filled Woolf with a sense of accomplishment. She continues in her December 13th entry:

And as I think I said before, it seems to leave me plunged deep in the richest strata of my mind. I can write and write and write now: the happiest feeling in the world.

Additional Resources

Visit the British Library's archives for access to Virginia Woolf's three volumes of The Hours/Mrs. Dalloway. The manuscripts are courtesy of The Society of Authors. Click on the images below for access to each volume.

In 1953, Woolf's husband, Leonard Woolf, published Virginia's diary excerpts that pertained to writing. The compilation covers 24 years of diary entries. All quotes were excerpted from the 2012 edition published by Persephone Books. A Writer's Diary: Being Extracts from the Diary of Virginia Woolf is an insightful read.

*Frontispiece

Close-up of Virginia Woolf's first page of Volume I of the Mrs. Dalloway manuscript. Courtesy of The British Library. © The Society of Authors