Charles Darwin: Evolution of the Origin of Species, Part II

"In July I opened my first note-book for facts in relation to On the Origin of Species, about which I had long reflected, and never ceased working on for the next twenty years." —Charles Darwin, Autobiographies

When Darwin returned from his voyage on the Beagle in 1836, he had by then embraced the notion of evolution. It would, however, take twenty-two years before he published his ground-breaking On the Origin of Species. Part I of Noble Ocean’s “Charles Darwin: Evolution of the Origin of Species” depicts Darwin’s first known attempt at articulating his theory in a cohesive essay in 1842. In Part II, we take a brief look at the 1858 manuscript of the Origin.

Draft of On the Origin of Species

"I have as much difficulty as ever in expressing myself clearly and concisely; and this difficulty has caused me a very great loss of time; but it has had the compensating advantage of forcing me to think long and intently about every sentence, and thus I have been often led to see errors in reasoning and in my own observations or those of others." —Charles Darwin, Autobiographies (1876)

Over the course of the twenty-two years that Darwin spent working towards what would eventually become On the Origin of Species, Darwin wrote multiple drafts. Part of the reason it took Darwin so long to publicize his work was that he was quite aware that his research would be considered heretical in the eyes of the Church and believers. Even more acutely, Darwin knew just how much the news would pain his wife, Emma. For both sides, a theory of evolution would suggest that there would be no reunion as husband and wife after death. It would also mean that after having ten children (three of whom died before the age of ten), there would be no hope of seeing them again.

There is something to this “background information” of the famed scientist. Somehow, as readers of history, we are prepared to view Darwin as a scientist preparing the strongest possible argument in preparation for backlash he might face. And yet, imagining him as a father and husband facing the personal implications of such a theory, we catch a theory placed within its time. Perhaps we are, too, reminded that ideas on paper, still to this day, have repercussions at the human element—that is, implications made not just to science, but to the social fabric of everyday thought.

The Family Man

This human element is so sweetly brought to life by the drawings that can be found on the reverse pages of the Origins. While writing his manuscript, Darwin gave his discarded pages to his children as drawing paper. Below one sees a fine cavalry of eggplant contra carrot.

These drawings can be found scattered through the Origins manuscript collection at the Darwin Manuscript Project.

Lighting the Fire

The culminating point within the process of publicizing his research on natural selection came when he received a letter from Alfred Russel Wallace stating a very similar theory and asking for Darwin’s advice. The Darwin Manuscripts Project explains the progression:

The text of the Origin of Species had a long history from Darwin's first sketch in 1842 to his final edition seventeen years later. After the first sketch he expanded it into the 1844 essay and wrote it out fully so that it could be copied and read by others. In 1856 at Lyell's instigation, he started writing a slightly expanded version of the 1844 essay with some significant additions to the argument, and as he wrote, the work grew into a much larger text which he planned to publish with the title of Natural Selection. In June 1858 when he had completed ten chapters of that book, he received the letter from Alfred Russel Wallace in which Wallace set out his own theory of evolution. After the joint announcement at the Linnaean Society of Darwin and Wallace's theories, Darwin wrote the 'abstract' of his theory to be published as the Origin of Species.

I imagine (with a bit of shared horror) what it must have been like for Darwin to receive a letter containing the very theory he had spent years refining. The 1858 letter from the young British biologist would send Darwin into top speed to publish the Origin. Prior to the publication, however, the two agreed to present their respective papers at a joint lecture at the Linnaean Society.

The content presented at the joint presentation by Darwin and Wallace can be found here. In honor of the role that Wallace played in this spurring of ideas, his work can be found here.

Additional Resources

Darwin amassed a large collection of drafts, notebooks, and letters related to his work on the natural selection. To see a range of work from September 1842-November 1859, visit this page from the American Museum of Natural History's Darwin Manuscript Project.

All of the images found here have been obtained through the American Museum of Natural History website through the Darwin Manuscript Project.

An excellent account of Darwin's sketches, outlines, notebooks, and publication history is collected in a short essay by Cambridge Digital Library.

Read about a group of hackers who made the Darwin Manuscript Project (housed at the American Museum of Natural History) possible.

Autobiographies includes a brief recounting of his life, but is especially rich for the insights he shares into his methodologies and writing processes. The edition below includes additional autobiographical fragments and is edited by Michael Neve and Sharon Messenger.

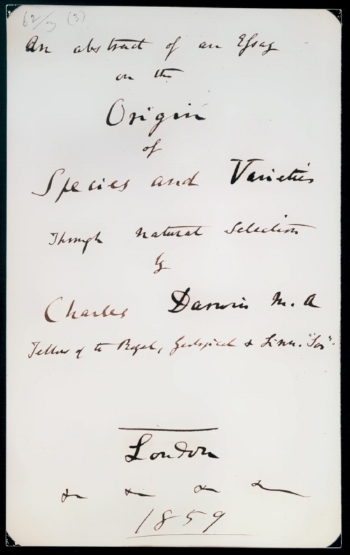

*Frontispiece

Prospective title for Origin of Species, March 1859, from Origin of Species 1st edition, draft. Reproduced with the permission of the American Philosophical Society and William Huxley Darwin. Transcription and apparatus © American Museum of Natural History